As someone who often struggled with self-control as a child and who is strongly resistant to being disciplined (even now; my twitter handle is undisciplined, after all), I bristled when I first saw the title of a recent op-ed from the New York Times: Teaching Self-Control the American Way. After reading the op-ed, which is about encouraging kids to regulate themselves and develop discipline through playing and engaging repeatedly in activities that they are passionate about, I found that I appreciate much of the authors’ ideas.

Primarily a reaction against disciplinary models that demand close supervision of kids and strict regulation of their behaviors and physical/mental practices (models that are exemplified and promoted by books like, Bringing Up Bébé), this brief article encourages parents to leave their kids alone, letting them play, pursue their own passions, and work their bodies so they can develop “cognitive flexibility” instead of the ability to rigidly follow rules and memorize facts. Sounds good to me! I’m a big proponent of play and letting kids follow their own passions. And I strongly believe that kids need to have space and time to exercise and be physically active. As a side note, I was struck by a line from the article: “Though parents often worry that physical education takes time away from the classroom…” Really? I find this sad to read that some parents want kids to have even less time for P.E. Furthermore, I love the idea of empowering kids to develop their own practices and tools for learning how to manage themselves.

But, while I appreciate the authors’ critique of rigid disciplinary methods and their emphasis on play, passion, exercise and harnessing kids’ own “internal motivations,” I still don’t like their repeated use of language like “self-control” and “discipline.” Why? This is a question that I’ve struggled with the past few years as I’ve developed and practiced my own vision of making and staying in trouble. Even as I promote trouble and embrace being undisciplined, I recognize the value and necessity of training, control and being able (and willing) to follow rules. With two children, I really recognize the value of following certain rules and being able to manage our bodies and emotions…like when we’re all in the grocery store and they’re just about to lose their shit because I won’t buy them [insert super-processed, fructose-corn syruped “fruit” snack here].

I’ve always deeply enjoyed engaging in repeated practices and building up skills. And I like rituals and habits, all of which seem to be important qualities of a person who can effectively manage/direct themselves responsibly and who is considered to have “self-control” and “discipline.” Throughout my childhood, I was actively involved in organized physical activities—5 years of ballet, a year of gymnastics, a year of basketball, 6 years of soccer, 5 years of swimming—and music—I played the clarinet and was in band for 12 years. I was also a diligent student with 26 (yes, 26: K-12, undergrad, masters, PhD) years of schooling. All of these activities have contributed to my vision of troublemaking as rooted in repeated practices and the building up of habits and skills. But, I would never claim to be disciplined and to have self-control.

Like I mentioned in the opening lines of this post, I bristle at these terms. Why is that? When I started writing this post yesterday, I don’t think I could have quite articulated why but now, having used the process of writing this post as a way to think, reflect and trouble “self-control” and “discipline,” I’ve developed a few reasons.

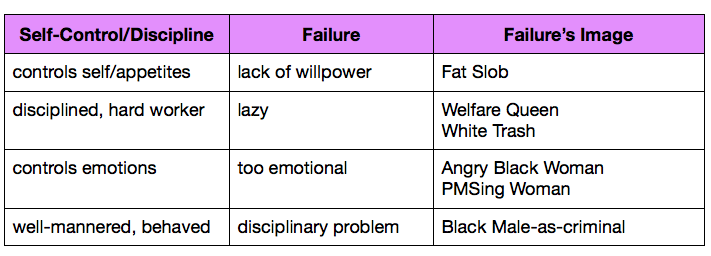

I refuse/reject/resist “self-control” and “discipline” because these terms, which are supposedly universal and objective, have become common-sense assumptions/Norms that we are encouraged to uncritically accept as givens without analyzing how they came to be accepted and at whose expense. This is evident in the New York Times op-ed. Throughout it, they argue for the value of self-control without ever clearly defining it; it is just assumed that we know what they mean. Sure, I agree with the idea that we need to encourage kids (and adults too!) to learn how to handle their emotions/reactions, to pay attention to rules/others/the world, and to develop strategies for surviving and thriving in the world (which all seem to be implied goals for acquiring self-control and discipline). However, when “self-control” and “discipline” are invoked, they frequently cite and reinforce particular images and understandings that are extremely damaging to a wide range of folks that fail to embody, in a wide range of ways, what Audre Lorde describes as the mythical norm or the assumed/implied Subject/Self (mythical norm = white, male, heterosexual, Christian, middle-classed, educated, thin, able-bodied, etc). I’ll go into more detail about what I mean here in a future post.

In addition to conjuring up damaging images and reinforcing problematic understandings of who is/isn’t able to have control and be disciplined, these terms are frequently linked to a particular set of conservative values (e.g. the first virtue in Bill Bennet’s The Book of Virtues is self-discipline) that are shaped by a very narrow vision of success/happiness that is unwanted and/or unachievable by many and that is privileged at the expense of a number of other, equally (or more) important values (like respect, attentiveness, vulnerability).

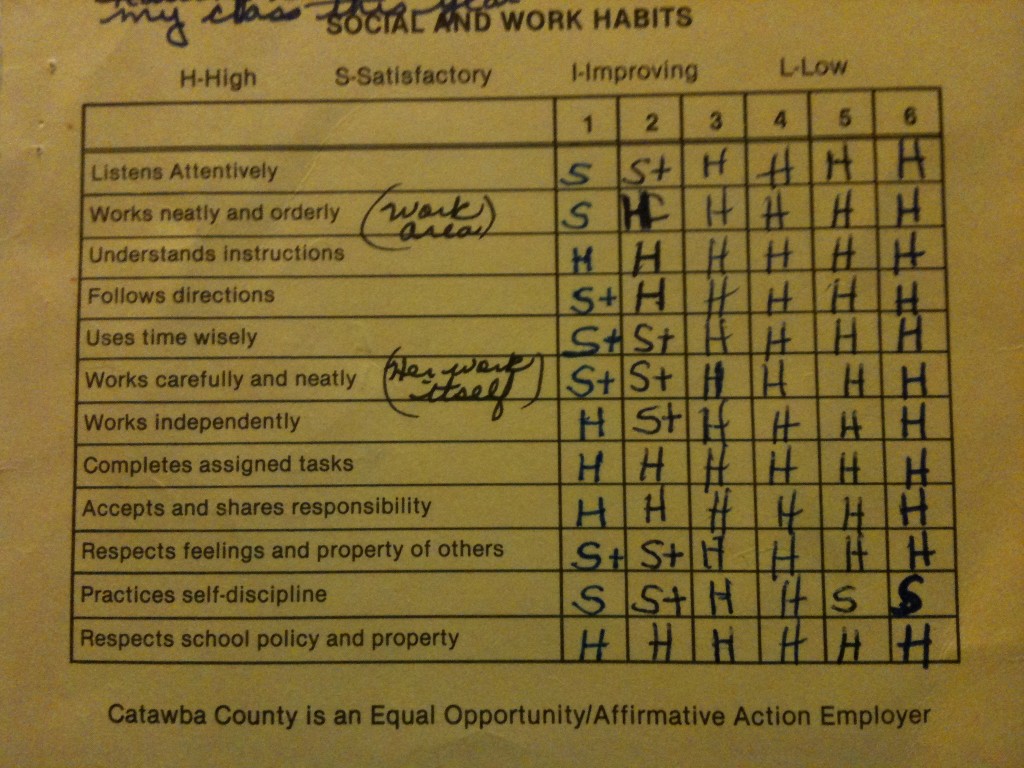

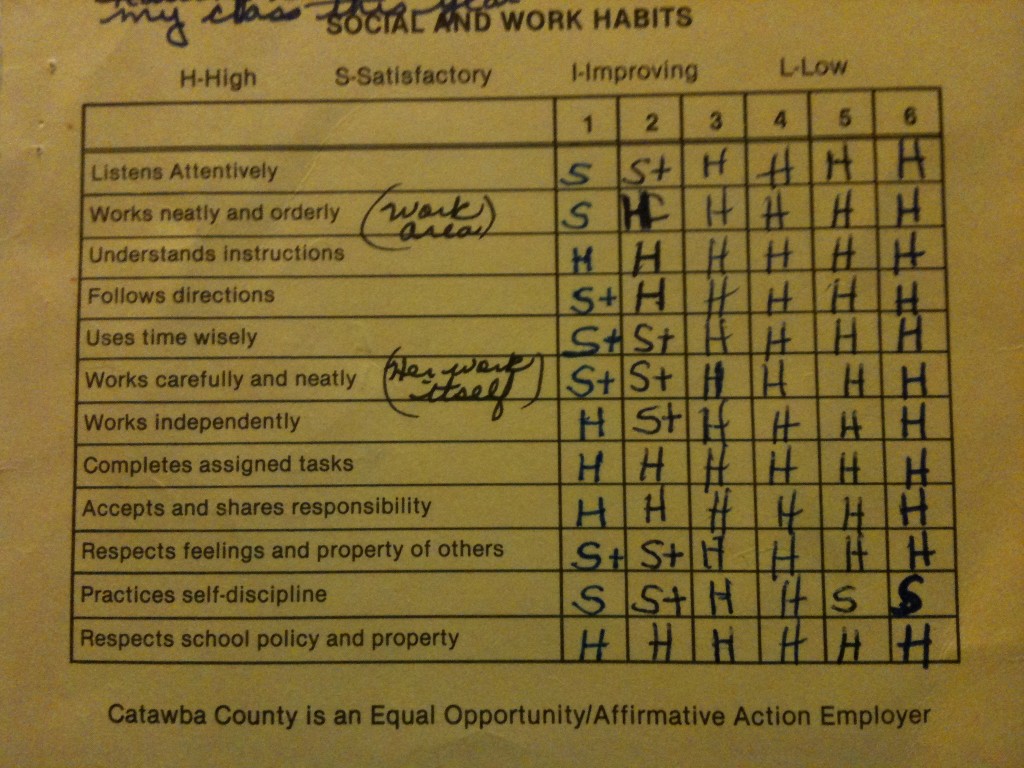

I want to spend time discussing all four of these (and probably more too) reasons why I refuse/resist/reject “self-control” and “discipline.” And I plan to in future posts. But, since I don’t have much more time today, I want to end with a screen shot of my report card (the only report card I still have) from 1st grade at Clyde Campbell Elementary in Hickory, North Carolina (in 1980-1981). The screen shot focuses on my “social and work habits,” which are all pretty decent. Notice that some of my lowest marks are for “practices self-discipline” (ha!) and my highest are for “accepts responsibility” and “respect.” Responsibility and respect are core values for me as an adult.