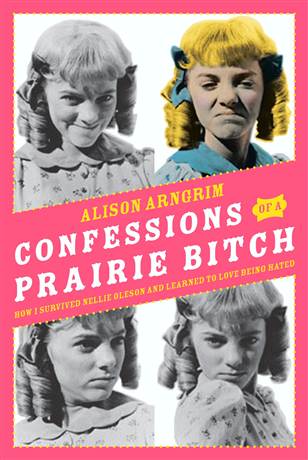

*Thanks to STA for pointing out this witty reversal. Originally I had titled this post, “Is Marcia Brady guilty of hubris or bad acting or both?”

Do you remember the episode of The Brady Bunch where Marcia is cast, against her will, as Juliet in her school’s production of Romeo and Juliet? She auditions for the role of the nurse but does such a “good” job that the drama teacher wants her to be Juliet. When she tells her family that she just doesn’t think that she is “the Juliet type” they hatch a scheme to convince her that she is worthy of the part. They repeatedly tell her she is pretty and smart and talented. Creepy moment alert: Greg even tells her that she is “a real groovy chick…for a sister, that is.” The plan works, but too well. Marcia becomes full of herself and begins to think that she is better than everyone else. When she argues with her parents about changing Shakespeare’s words, Mike remarks: “First the part’s a little too big for her. Now I think maybe she’s a little bit too big for the part.” Woah….Mr. Brady is deep. After she causes more trouble (yes, this is the word that is used to describe her actions)–like ridiculing her Romeo and talking back to the drama teacher–Carol decides that drastic measures must be taken. Without consulting Marcia (or even having any serious or lengthy conversation with her about why she was causing/being trouble), Carol and the drama teacher kick Marcia out of the play. Bad acting alert: Although it would be very easy to argue that Maureen McCormick’s acting is terrible throughout this episode, the piece de resistance comes at 22 minutes and 24 seconds when Carol reveals to Marcia that her name isn’t in the final program. Wow!

Do you remember the episode of The Brady Bunch where Marcia is cast, against her will, as Juliet in her school’s production of Romeo and Juliet? She auditions for the role of the nurse but does such a “good” job that the drama teacher wants her to be Juliet. When she tells her family that she just doesn’t think that she is “the Juliet type” they hatch a scheme to convince her that she is worthy of the part. They repeatedly tell her she is pretty and smart and talented. Creepy moment alert: Greg even tells her that she is “a real groovy chick…for a sister, that is.” The plan works, but too well. Marcia becomes full of herself and begins to think that she is better than everyone else. When she argues with her parents about changing Shakespeare’s words, Mike remarks: “First the part’s a little too big for her. Now I think maybe she’s a little bit too big for the part.” Woah….Mr. Brady is deep. After she causes more trouble (yes, this is the word that is used to describe her actions)–like ridiculing her Romeo and talking back to the drama teacher–Carol decides that drastic measures must be taken. Without consulting Marcia (or even having any serious or lengthy conversation with her about why she was causing/being trouble), Carol and the drama teacher kick Marcia out of the play. Bad acting alert: Although it would be very easy to argue that Maureen McCormick’s acting is terrible throughout this episode, the piece de resistance comes at 22 minutes and 24 seconds when Carol reveals to Marcia that her name isn’t in the final program. Wow!

There is much that I could write about this episode (such as: Alice revealing that she went to an all girls school and performed–in drag!–as Julius Caesar). Well, I might just have to write about that later. But, in this post, I want to think about Marcia’s behavior, the Brady family’s scheme to build up her self-esteem and the troubling consequences of that scheme. And, I want to think about of this in relation to virtue ethics, moral education and Mike’s and Carol’s continued efforts to earn “the worst parents in the history of the world” award.

There is much that I could write about this episode (such as: Alice revealing that she went to an all girls school and performed–in drag!–as Julius Caesar). Well, I might just have to write about that later. But, in this post, I want to think about Marcia’s behavior, the Brady family’s scheme to build up her self-esteem and the troubling consequences of that scheme. And, I want to think about of this in relation to virtue ethics, moral education and Mike’s and Carol’s continued efforts to earn “the worst parents in the history of the world” award.

Nice. So, Marcia doesn’t want to be Juliet. Instead, she is happy to be cast as the nurse. Or, is she? According to Mike and Carol, she really wants to be the star, the beautiful and noble Juliet; she just doesn’t have enough self-esteem. She can’t see herself the way others do: as a “real groovy chick.”

Mike: You look beautiful and noble to me.

Carol: The trouble is, you don’t think you are.

Mike: That’s right. It’s your belief in yourself that counts, you know. You are what you think you are.

Marcia: You mean, if I think I’m beautiful and noble than I will be beautiful and noble.

Mike: That’s right. If you believe it, everybody will believe it too!

Ah ha! The trouble is that Marcia has a low opinion of herself (of course it couldn’t be that she actually wanted the role of the nurse–a pivotal and interesting, yet less glamorous role). What she needs, according to Mike and Carol is “the power of positive thinking!” That will get rid of her troubles! But when she starts thinking positively, more–and perhaps more serious–trouble is the result. She begins not only to believe in herself but to believe that she is the best; she is noble with an elevated status that makes her better than everyone else. She demonstrates this through shameful acts of hubris (and yes, she acts badly…and badly acts).

But, what really has caused this hubris? Here is a series of related questions that trouble me:

- Is her hubris the result of an excessive display of pride/a deficient display of humility?

- Or, is it the necessary (and logical) result of the Brady family’s approach to building up her self-esteem?

- If there are some bad actions (and bad acting too!) in this episode, who is doing them? Is it really Marcia, who is following the advice of her parents to truly believe that she is noble and beautiful?

- Or is it Mike who encourages her to be beautiful and noble but equates that with being a star and thinking (too) highly of herself and fails to give her any substantial definitions of beauty that are counter to societal standards? (Standards that are often driven by capitalism and our role as consumers. And that discourage girls from ever thinking that they are beautiful enough. After all, if you think you are beautiful, you wouldn’t ever need to buy any products right?)

- Or Carol who promotes a decidedly superficial vision of “the power of positive thinking” that is not connected to any underlying ethic or understanding of how our positive (and negative) thinking has real just and/or unjust effects on others.

I suppose you know where I am going with this. Yes, Marcia does act badly. And yes, she does badly act. But, it is Mike and Carol who really act badly in this episode. The moral education that they offer to Marcia (and by extension, to us) is just plain bad. Marcia is encouraged to think positively about herself, but she is never given any guidance about how exactly to do that. Mike and Carol want her to build up her character, to make it (and her) more beautiful and noble. They don’t, however, give her any guidance on how to make her character virtuous. That is, they give her no strategies/skills/advice for what kinds of actions she should engage in. And they fail to support their advice with any underlying moral vision or ethical system that could guide (or temper or foster) that positive thinking.

When Carol Brady praises Marcia’s new found belief in herself (at the beginning of Marcia’s diva period) as “the power of positive thinking,” she is referencing a very watered-down, overly simplified, faithless, pop psychology version of Norman Vincent Peale’s wildly popular self-help book, The Power of Positive Thinking. Carol’s advice seems to fit this equation: Power of Positive Thinking – ethical vision or virtue ethics = Marcia-as-major-diva.

While I was searching for an image of Marcia to use for this post, I came across an entry entitled, “The Hubris of Marcia Brady” on The Brady Bunch Blog. For a different take on Marcia, check it out.