In the past 24 hours, I’ve encountered several online discussions about privilege (especially, but not exclusively white privilege). I want to archive these conversations for future reflection.

Encounter One: Scrolling through my politics of sex course blog from last semester last night, I came across my lecture notes on privilege. Here they are:

Today’s topic for discussion is privilege and oppression. This is a continuation of our discussion on Monday about heteronormativity and straight thinking. Ingraham writes:

The question then becomes not whether heterosexuality is natural, and therefore ‘normal’, but, rather how do cultural meaning systems work to normalize and institutionalize heterosexuality? And, more importantly, what interests are served by these processes? In other words, who benefits from the ways we’ve named, defined, and organized sexuality (74)?

- Audre Lorde in “Age, Race, Class and Sex” in Sister Outsider: “Somewhere, on the edge of consciousness, there is what I call a mythical norm, which each one of us within our hearts knows “that is not me.” In america, this norm is usually defined as white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure. It is with this mythical norm that the trappings of power reside within this society. Those of us who stand outside that power often identify one way in which we are different, and we assume that to be the primary cause of all oppression, forgetting other distortions around difference, some of which we ourselves may be practising.”

- Kate Bornstein in My Gender Workbook: The pyramid

- Not just about any one category, or about envisioning the problem as one of binaries: oppressed/oppressor, white/non-white, male/female.

Instead, about a larger network of norms (in terms of race, class, religion, gender, sexuality) that together contribute to this larger power pyramid of status/identity/privilege

LINKING INDIVIDUAL ASSETS AND MICROAGGRESSIONS WITH LARGER STRUCTURES OF PRIVILEGE AND OPPRESSION

- Not isolated instances or individual practices of a few “bad” people

- When analyzed cumulatively we can begin to see larger structures that enable the systematic oppression of groups who don’t fit the mythical norm/who fall outside the normal. What structures do you see emerging in these lists?

- While becoming aware of privilege and microaggression involve individual experiences and encourage individual reflection, they are not about our individual intentions or about who we are (it’s not about us). Instead, awareness of privilege, microaggression and oppression is about the effects and affects of our actions/understandings on others. And how those actions are made in a larger context and social/material/historical processes of meaning-making.

- Individuals/groups learn/are taught how to ignore privilege and to take it for granted

- This learning process involves being discouraged from thinking critically about race, sex, gender, class.

- It also requires active refusals to become aware and to engage in critical thinking.

- Learning process trains us how to engage in practices of racial/sexual/gender/class/ability/ethnic microaggressions. We may engage in these wittingly and unwittingly.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? WHAT’S THE PURPOSE OF EXAMINING PRIVILEGE/MICROAGGRESSION?

- Importance of discomfort in addressing these issues

- Why study micoraggressions? Privilege?

- What do we do with this knowledge?

What do you think about this statement “about this site” on the microaggressions blog?:

This project is a response to “it’s not a big deal” – “it” is a big deal. “it” is in the everyday. “it” is shoved in your face when you are least expecting it. “it” happens when you expect it the most. “it” is a reminder of your difference. “it” enforces difference. “it” can be painful. “it” can be laughed off. “it” can slide unnoticed by either the speaker, listener or both. “it” can silence people. “it” reminds us of the ways in which we and people like us continue to be excluded and oppressed. “it” matters because these relate to a bigger “it”: a society where social difference has systematic consequences for the “others.”

but “it” can create or force moments of dialogue.

A few more resources:

- There are lots of privilege lists circulating on the interwebz. Here’s a list of many of them.

- Check out these, in particular: The Black Male Privileges Checklist and Daily Effects of Straight Privilege (by Peggy McIntosh) Why are there so many privilege lists available? What are the benefits and limits of such a proliferation of lists?

- Check out this critical assessment of the privileges approach: “The Color of Supremacy: Beyond the discourse of “white privilege”

Encounter Two: Woke up this morning and checked my twitter feed. I found a tweet via @racialicious about a post on racism vs. white guilt.

This video is the subject of her post:

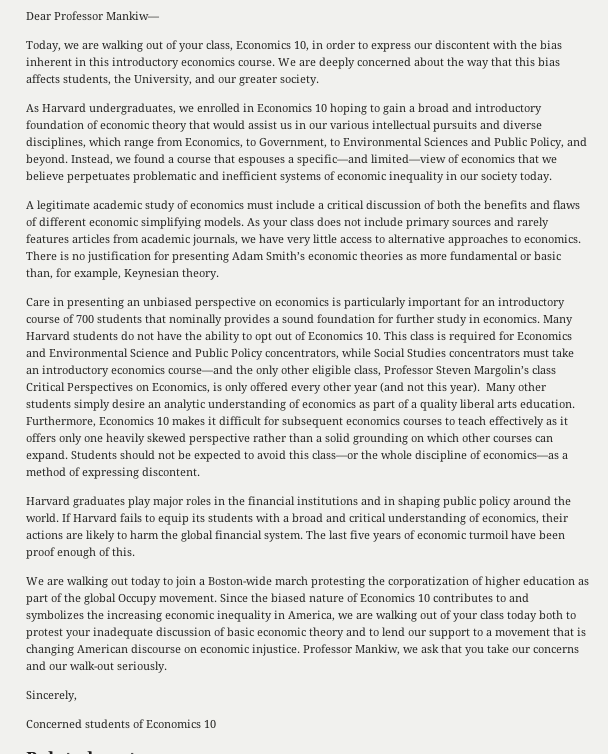

Encounter Three: After encountering my notes and the video on white guilt, I remembered that Slutwalk Toronto was planning to post on privilege soon. We’ve been following Slutwalk in my feminist debates class all semester and read/discussed their statement on racism in class a few weeks ago. I checked their blog this morning and found it: What’s All This About “Privilege”?