Last night, I watched the Halloween episode of Parks and Recreation. One of the characters, Donna, did a lot of live-tweeting. Awesome.

Month: October 2012

Playful Resistance through Online Reviews

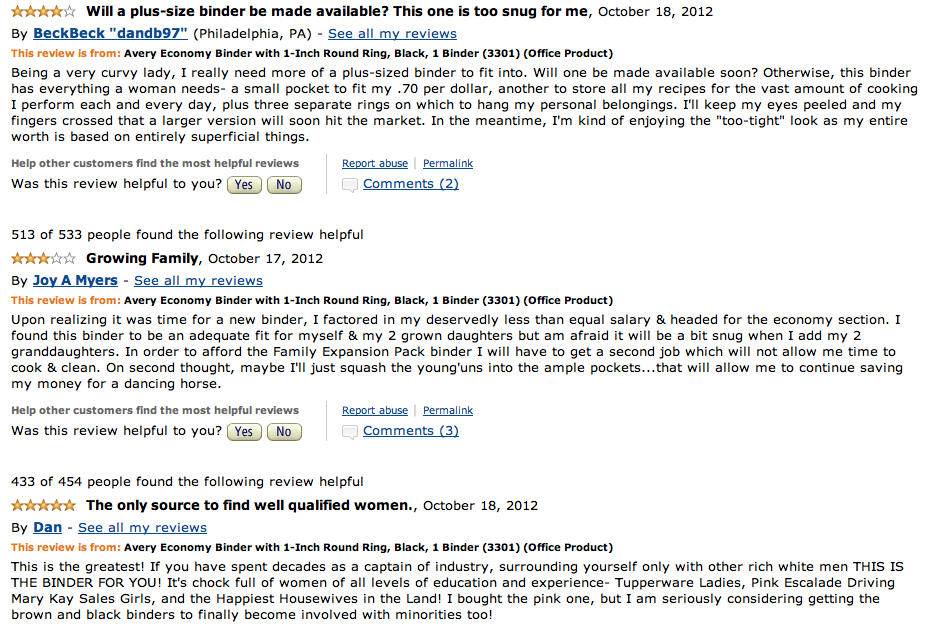

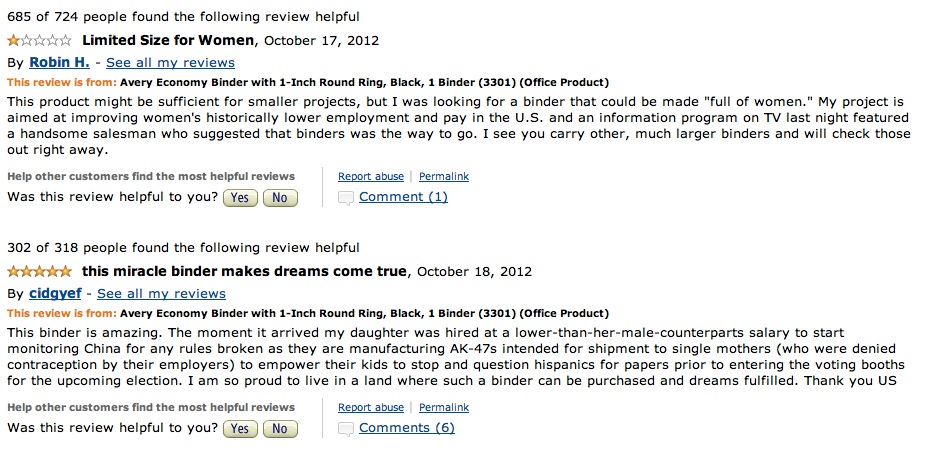

Recently, I’ve noticed a creative and playful approach to subverting, challenging and resisting oppressive norms and the people, institutions or products that promote them: writing a critical/humorous review of a product online. How long has this been going on? I’m not sure, but I started to see them right after the second presidential debate and Romney’s “binders full of women” comment:

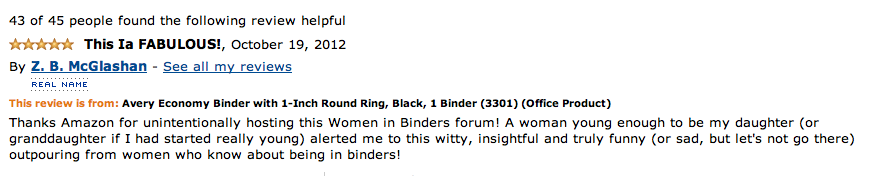

There were all sorts of excellent critical responses to Romney’s ridiculous comment; Tumblrs, twitter accounts, memes were created even before the debate was over. For a good overview, check out Binders Full of Women: Know Your Meme. While it was great to see so many different creative and critical ways in which to respond to Romney, I was particularly struck by the online reviews of binders on Amazon that playfully resisted and challenged Romney’s remark. Here are just a few, found on the review page for an Avery economy binder:

I scrolled through at least 8 pages of these and they were all reviews that explicitly addressed the Romney comment. Not all of the reviews offered a critical/feminist critique of women’s roles in the workforce, but most of them did, like these:

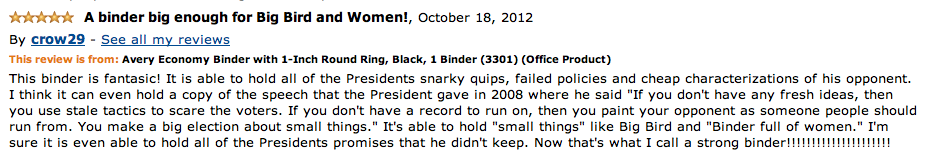

I should note that around page 24, Romney supporters/Obama critics began posting their responses. On the whole, these responses did not seem to adopt the humorous approach and were aimed directly at critiquing President Obama and not addressing or clarifying Romney’s extremely problematic record on women’s issues. Here’s an example:

Spending time this Monday morning looking through and thinking about these reviews, has made me curious and prompted to pose many questions.

Questions

How did this review intervention begin? Were the acts of resistance/critique spontaneous? Did the first review inspire others to leave their own “binders full of women” reviews?

What impact did/does/will these reviews have on voters, especially women voters?

Are these reviews forms of resistance? Are they, as Time Magazine’s article on them suggests, a snarky joke? How/when can snark and humor be used for critique and talking back?

Do Republican/Romney supporters engage in playful and humorous critiques of the debate? Where? How? What do these look like? What tone do they take?

What is the relationship between critical thinking and consumerism going on here? What do these reviews “do” to our understanding of consumerism and to our expectations concerning online stores and what we will find or do on them?

Why did people take up the “binders full of women” comment instead of Romney’s discussion about how women staffers could go home earlier so they’d have time to cook dinner? Would the latter have been more effective than the former in generating a critical and disruptive meme?

In general, I’m fascinated by the various playful responses to the Presidential debates. I’m still thinking through what I think of these reviews and the “binders full of women” meme. Here are a few of my tentative conclusions:

Tentative Conclusions

Without social media, especially Tumblr, where I first heard about then, I wouldn’t know about these resistant reviews. I’m sure they have shown up on twitter feeds and facebook timelines for lots of people too. While this might seem like an obvious point, it’s important to note the impact of social media on how many of us process, engage with and understand the Presidential election season. Social media can provide many of us (but not all) with access to alternative (as in, alternative to mainstream media’s talking heads and endless polls) sources and spaces for reading, producing and sharing content.

These resistant reviews enabled strangers to temporarily create a safe space for sharing frustrations about larger systemic problems concerning women and work and about Romney’s troubling approaches to women’s issues. On page 8, I found this review:

These spaces weren’t safe (anyone could read them and able to post their own snarky responses). However, they did provide a way to make visible the experiences and feelings of women who aren’t just resumes (objects) collected in a binder and who shouldn’t just be talking points for the candidates. In talking back through their reviews, these reviewers attempted to hold Romney accountable for the less-than-truthful (bullshit) claims that he was making and how they did/did not accurately reflect his past actions and his proposed policies as president.

These are not grand refusals, but, in the spirit of Michel Foucault, small acts of resistance that have the potential to subvert and disrupt. They become more significant when we think about them in the context of the wide range of ways that debate viewers (and followers of the debate through twitter or facebook), critically engaged with the debate.

Playful and humorous responses to the candidates like these reviews are an opportunity to have important conversations about the nature of resistance and its relationship to humor, how/where resistance is possible through social media, and how Romney and Obama address and think about women.

Note: This isn’t the first time that resistant reviews have shown up on Amazon. Reviewers also talked back to the Bic’s for Her Ballpoint Pen.

Free to be…you and me: 40th Anniversary

This November is the 40th anniversary of Free to be…you and me. The television special, which aired on March 11, 1974 (3 months before I was born) and was shown repeatedly in my elementary school in North Carolina, was my introduction to feminism. In honor of the anniversary, I thought I’d post some of my online lectures about the film; I’ve screened parts or all of it in many of my classes.

Feminist Debates, Fall 2011

Final day of class, December 13, 2011

In “Feminist Education for Critical Consciousness” (in Feminism for Everybody), bell hooks argues for the need to give children access to a feminist education. Is this possible? Necessary? What would it look like? Did you have access to feminist education when you were younger? If so, what were (weren’t) you taught?

On our last day, I thought I’d show you my introduction to feminist/feminist values: Free to be…You and Me.

I’m a child of the 1970s (born in 1974). When I was in elementary school in North Carolina, the entire school watched the Free to be…you and me film (Videos/VCRs didn’t exist yet…yes, I’m that old) during an assembly. Everyone was really excited because it was a long film–a whole 45 minutes!–and long films meant less class time. Anyway, I don’t remember much of what I thought about the film back then (I was probably 6 or so). Yet, I’m sure some of it seeped into my consciousness, helping shape how I experience the world and how I see myself and my relationship to others.

I’m a child of the 1970s (born in 1974). When I was in elementary school in North Carolina, the entire school watched the Free to be…you and me film (Videos/VCRs didn’t exist yet…yes, I’m that old) during an assembly. Everyone was really excited because it was a long film–a whole 45 minutes!–and long films meant less class time. Anyway, I don’t remember much of what I thought about the film back then (I was probably 6 or so). Yet, I’m sure some of it seeped into my consciousness, helping shape how I experience the world and how I see myself and my relationship to others.

Originally a book/album created by Marlo Thompson, with a little help from Gloria Steinem, Free to be…you and me was turned into a one hour TV special. It first aired March 11th, 1974 (3 months before I was born). You can find out more about the history of the project here. Several years later, it became a popular film to show in schools around the country (like mine in North Carolina. It was also shown in Minnesota).

It stands as one example of feminist mass-based education. Would such a show be possible now? What sorts of feminist (or feminist-friendly) films did you see in elementary school? If we were to create a feminist resource for kids, what would/could/should it look like?

Here’s one of my favorite songs from the show:

Feminist Debates, Spring 2011

April 11 Youth/Children and Values

Readings:

Martin, Karin. “William Wants a Doll”

Berstein, Susan David. “Transparent”

film clips: Free to be…you and me and Tomboy

Direct Engagement Question for the week (students were required to post comments on these questions):

- What does it mean to engage in gender-neutral child rearing?

- How are gender and sexuality connected in terms of child rearing and the development of gender identities? This is a key part of Martin’s argument–I am curious about what you all think she is saying with this argument and if you agree with it or not.

- We will be watching the clip from Free to be…you and me, “William Wants a Doll” in class on Monday.

You can check out the lyrics here). What sorts of strategies (theories of gender, etc) are going on in this song? What do you think about how this song frames William’s behavior in terms of his role as a father? - In her essay, Martin describes one of the critiques made against socialization theory, that it offers an “exaggerated view of children as unagentic, blank slates” (457). (How) are children active participants in their gendering process? How do they process and reflect on their own gender performances (their practices, actions, etc)? Are they just products of socialization? Or, are they both projects of socialization and agents who negotiate their gender identities/roles/expectations?

We wil be watching this video in class today:

Tomboy from Barb Taylor on Vimeo.

Here are some questions to consider from kjfalcon’s discussion of the movie:

- What are some of the main messages from the cartoon?

- Why is gender something that has to be policed?

- In the cartoon how do you interpret the representation of the intersections of gender and race? If you don’t see the explicit connection between gender and race/ethnicity does it matter that this Alex – the tomboy – is a Latina character?

- What do you think of the representation of the mother character?

- This is meant to be a tool for teachers learning how to teach – is this affective in this sense? What value do you see in encouraging dialogues around these issues to occur through this movie?

Comments (on blog entry)

Nosecage | April 15, 2011 1:20 PM

I am going to try to keep this comment relatively brief, as I know we all have so much work to be getting done. I was, however, a little bummed that we didn’t get to address “Transparent” by Susan Bernstein in class last week. I think it’s a really important article to critique and engage with, so I wanted to bring some of my curiosities up here on the blog and see if we could have a bit of a discussion.

My main concern here is that we understand that Bernstein’s perspective is quite problematic on a couple of levels. The article is not meant to be taken as an authoritative perspective on what it means to raise kids with gender-neutral values. Bernstein does nothing to address the consequences of her kid’s gender non-conforming behavior, which can be severe and damaging. Throughout the article, Bernstein writes from a stance that suggests an almost utopic (not-a-word; adjective form of ‘utopia’) understanding of the world. As early as the third paragraph she says, “…it’s a commonplace to encourage children to try on all sorts of identities.” Really? I think not.

She at one point explains to Nora (her daughter) that, “…once in a while boys grow up and decide to be women, and the other way too.” This seems like an overly simplistic description of transgenderism, if not outright misinformation. Most transgender folks I know don’t ‘decide’ to be transgender, or to transition to living as some other gender than they were assigned at birth, it’s something they need to do in order to begin the process of being comfortable with their bodies–which I would argue is an undeniable human entitlement. While I understand that some of the complexities might be hard to put into language that young children can comprehend, it’s important to not set them up with assumptions that could potentially lead to transphobia (“If they’re simply deciding, why don’t they just not do it?”) Is this all we can say to kids to trouble sex/gender assignment? Can’t we work outside gender binaries to ensure our children have a full range of ways of expressing their gender and, more importantly, their personhood?Perhaps even more troubling is the way Bernstein deals with and addresses Nora’s eventual move toward gender conformity. She praises Nora’s androgyny as if it were the ultimate answer to gender troubling–some phase on the path to personhood at which we can all arrive and feel at ease. Bernstein also largely ignores the question of Nora’s sexuality, which clearly deserves to be addressed.

Finally, the second to last sentence of the article, “Today’s multiplication of options, though inevitably a challenge, definitely bespeaks a better chance for adult postgender happiness,” almost critiques itself. Bernstein’s uptopic vision is made so apparent in this sentence that I’m not even sure what else to say. Postgender!? Equivalent to color-blindness!? Eek.

sara | April 16, 2011 10:32 AM

Thanks, nosecage, for beginning this discussion. I agree that it is important to be critical of this essay and I think you do a great job of raising some key points of concern. As I was reading this essay, I also found myself writing all over the margins: what about the consequences of violating gender norms? In many ways, this story of Nora seems very utopic. The recent s**tstorm over a boy wearing pink nail polish demonstrates that “playing with gender norms” has serious consequences–consequences which are exacerbated by social media and the ability to spread violations so rapidly and effectively across the interwebz.

I also agree that sexuality needs to be a big part of this discussion. In many ways, Bernstein’s essay and her promotion of postgender happiness seems to be an extension of the second wave gender-neutral parenting techniques and the “free to be…you and me” attitude that was always haunted by heteronormativity and the threat of homosexuality (this gets hinted at when Bernstein discusses Nora’s “baby dyke” haircut on page 4). How are negotiations of gender tied to negotiations of sexuality?

This essay is from the perspective of Nora’s parent and not Nora. What might Nora’s narrative about growing up and negotiating the gender binary look like? How might she talk about the experience of being mis-identified at the hotel or being accused of being in the wrong bathroom? We focused our discussion on family values from the perspective of feminist parents and their attempts to educate kids/youth. How can youth be engaged in the process of educating? Check out Put This on the Map and their video about reteaching gender and sexuality (created in the wake of the It Gets Better Campaign from last fall).

Paul Goodman, troublemaking role model?

This morning, I finally finished watching the documentary, Paul Goodman Changed My Life. I had heard about it on twitter from one of my favorite tech-ed troublemakers, Audrey Watters (Hack Education). I’m not sure if I would call Goodman a troublemakng role model (hence the question mark in the title of this post), but I enjoyed learning about his life and his ideas. I want to think about it some more, but my initial hesitancy in identifying him as a role model involves how limited his caregiving for others, especially members of his own family, seemed to be. His version of troublemaking involved a relentless pursuit of the truth that lacked a consideration of the impact of that pursuit on specific, concrete others.

But, even if I don’t subscribe to his specific vision of making trouble, I enjoyed learning about it and Goodman’s life/writings.

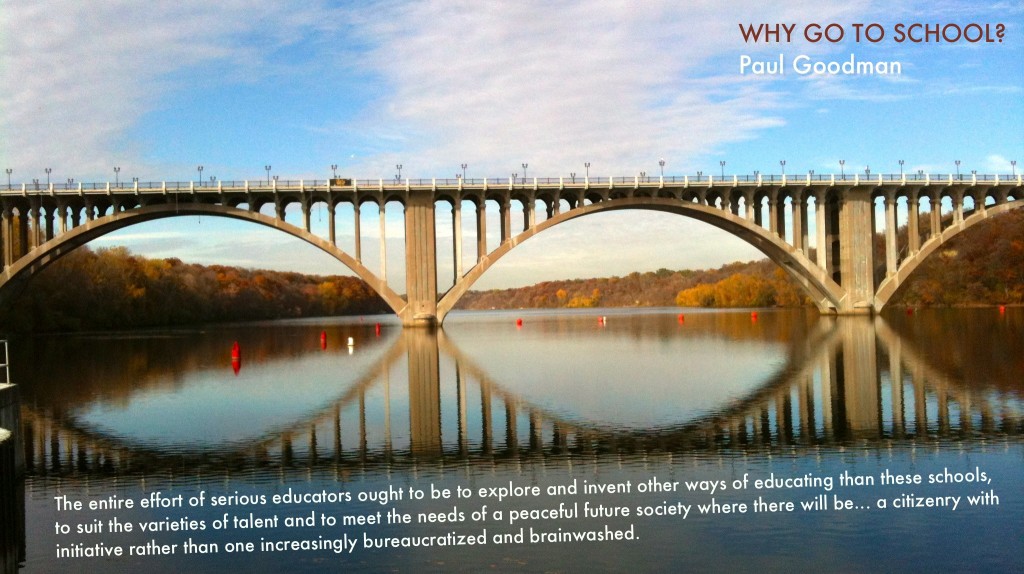

In her tweets about it, Audrey Watters also mentioned Goodman’s 1963 essay, “Why Go to School?” Goodman poses it as a challenge, not an explanation. He writes:

To sum up: all should be educated and at the public expense, but the idea that most should be educated in something like schools is a delusion and often a cruel hoax. Our present way is wasteful of wealth and human resources and destructive of young spirit.

The question, “Why go to school?” is one that resonates with me right now. Up until a few years ago, I never doubted that school was important, necessary and valuable. As a kid, I loved learning and going to school, even as I didn’t get along with several of my teachers. But, recently I have started to question the role of school as the primary location for learning. I don’t completely agree with Goodman’s claim that school is for many, “a delusion and often a cruel hoax.” However, I do wonder if schools, especially at the University/college level, can effectively prepare students to survive/flourish in the 21st century networked world. And I wonder what happens to other ways of knowing, learning and engaging when so much emphasis is placed on earning overpriced degrees.

One passage from Goodman’s essay inspired me to create a new Problematizer:

Here is the full passage:

The entire effort of serious educators ought to be to explore and invent other ways of educating than these schools, to suit the varieties of talent and to meet the needs of a peaceful future society where there will be emphasis on public goods rather than private gadgets, where there will be increasingly more employment in human services rather than mass-production, a community-centered leisure, an authentic rather than a mass-culture, and a citizenry with initiative rather than one increasingly bureaucratized and brainwashed.

As I read through this passage (and recall the rest of the essay), I am reluctant to fully agree. Yet, even as I reject Goodman’s extreme position, I’m find myself unable to offer convincing answers to his provocative question: Why go to school?

Curiosity and Being Engaged

According to Connie Yowell, Director of Education at The Macarthur Foundation, “Part of what’s wrong with the educational system and why people talk about it as broken is because it’s fundamentally starting with the wrong questions.” In this short film by Nic Askew, Yowell argues that we need to shift our question in education away from “what are the outcomes?” and toward “is the kid engaged?”

ENGAGED from DML Research Hub on Vimeo.

This video is part of a series of videos by Nic Askew on “The Essence of Connected Learning.” Yowell argues that if we focus on the question, “is the kid engaged?” we are compelled to pay attention to that kid as a person, not just a student/test-taker. Then we can develop strategies for reaching the kid and getting them excited about being curious, learning, and developing a strong “need to know.”

Here’s one of my favorite points:

In the traditional school system, where we’re driving home facts and discrete knowledge, we don’t make room for curiosity. We don’t create enough opportunities for kids to take things apart anymore. To look inside. To see how they’re made. To put them back together again. We used to do it with our old chemistry sets. We used to just play and see what would happen and wonder about it. That engages the imagination and can trigger the imagination. As we get more and more serious about test scores and our kids future, we move further and further away from those little opportunities to constantly fail and to iterate. And we forget that those are also opportunities to iterate with one’s identity. And to play around and to mess around. And it’s so important to do that when you’re at the middle school age and your early in adolescence—even when you’re an adult. We’ve gotta have these opportunities to be curious about who we are in the world and about how the world works and to fail and not be embarrassed by it. And to come back to those failures and do things over and over again.

I love the idea of focusing on failure and being curious and linking both of these to imagination and understanding about the world. But, how do we make room for these? What would a classroom (or a workplace) that embraced (valued, encouraged, celebrated) failure look like? Is that something that the teacher should model?

I think that feminist and critical pedagogies, with their focus on engaged students who actively participate instead of passively receive (Freire) and who embrace their discomfort and unknowingness (Megan Boler) would add a lot to this conversation. Also, bell hooks and her emphasis on bringing the whole person (mind, body, spirit) into the classroom would be helpful. At one point in the video, Yowell argues that we can’t force students to learn facts; we need to find ways to inspire and incite their “need to know.” Using her son as an example, she describes how he doesn’t care about fractions at all in school. But, if he’s in the middle of a game, and he needs to know how to solve a fraction in order to move onto the next level, he demands that someone teach him. I really like this idea. Building off of Yowell’s conversation, I think it’s important to pay attention to what, beyond an outcome-based, test-driven model, prevents kids from being curious and “needing to know.” What other factors contribute to an unwillingness or resistance to knowing? Here I’m thinking of lots of different things—everything from lacking energy/desire to know because you’re hungry or too tired, to being wary of what knowing might do to us (see Luhmann for more on what knowledge does to us.) To me, these questions come out of a need to pay attention to power and privilege.

In posing these questions, I was curious about whether or not other videos in the series addressed these issues of dealing with barriers to developing a “need to know” in terms of power and privilege (which is what feminist pedagogy devotes a lot of energy to). While the other videos are great—I especially like Creative—and they make oblique references to opening up education to “everyone” and moving beyond the top 10%, discussions of sexism, classism, racism, or heterosexism don’t seem to be explicitly referenced. Why not? Is this lack of reference to feminist and critical pedagogies indicative of larger conversations at DMLCentral: Digital Media and Learning? I’ll have to look through more of their videos and check out their site to see…