I just posted the bulk of my introduction to my intellectual history over at Undisciplined. I thought I’d post it here too:

Welcome to my intellectual history project. In these pages, you will find a series of essays/accounts/fragments about my life as a student. While a few of them concern my earliest years in kindergarten and first grade, the bulk of them are from college, graduate school and my post-Ph.D teaching and researching (1992-2011). Collectively, they represent my efforts: 1. to make sense of my current status as existing somewhere beside/s the academy and 2. to experiment with ways to bring myself into my academic work on subjectivity, agency, narrative selfhood and storytelling.

I. Origins of this Project

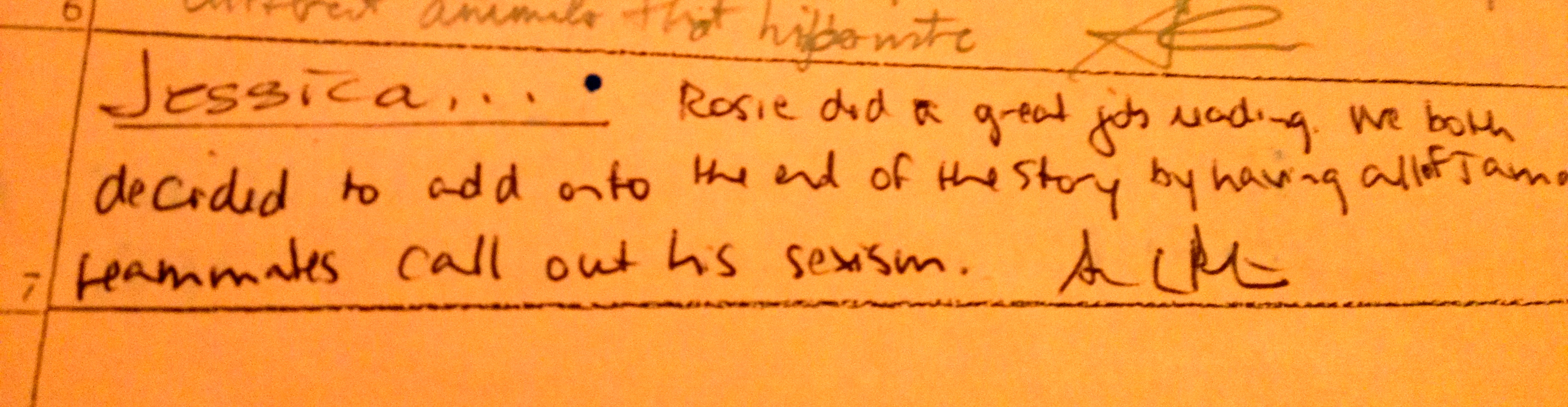

My efforts to reflect on and write about my experiences as a student in the academy have been happening for over three years on my blog, Trouble. But, I didn’t envision making them the focus of a singular writing project until this past fall (my first fall since I was 5 that I hadn’t been in school as a student or teacher), when I started creating tentative outlines of my autobiography and brainstorming information architecture for my new website, Undisciplined. Then, in December of 2012, when I was sorting through my old files and organizing papers that extend all the way back to college (1992-1996), I realized that I wanted to write a series of accounts in which I used my own archive as the source material for critical reflections and interrogations of life as a student in the academy.

As I began digging through my files in the basement for documents that seemed significant, I was relieved to see that even though I had moved around quite a bit as a student—from Minnesota to California to Minnesota to Georgia to Minnesota again—I had managed to hang onto some key documents: the final evaluation for my senior thesis, a copy of my master’s proposal, papers (with my teacher’s comments) from my first year in college, name tags from conferences, old student ids. I also explored my digital files, searching through hidden folders (that I only managed to find after trying out different keyword searches), dating back to my masters, and discovered past papers, presentations, my senior thesis, my master’s thesis and my dissertation.

Looking back at these materials, both the physical and the virtual, conjured up a mix of emotions that made me feel joyful, sad, nostalgic, angry, and conflicted all at once. I had done so much work over the years. Amassed so many articles, all carefully organized with printed-out labels, on feminist theory, identity politics, poststructuralism, feminist and queer pedagogies, feminist theology, ethics, radical democracy, queer theory, critical race studies and more. But even as I marveled at my dedication as a student and scholar, I was troubled by how this work was all in the past—I had stopped teaching and doing “academic” research in December of 2011— and haunted by the questions: What was this work for and why had I stopped?

In order to spend time working through these questions, not so much to answer or resolve them, but to learn to live with the discomfort and uncertainty that they generate, I started writing. The first account I wrote was “Pithy Chewiness.” Then, inspired by the process, I wrote, “Promise.” I began looking through past accounts I had already created on my blog or in digital stories and combining those with new reflections. I read through old papers and wrote about how my perspectives as an undergraduate or an early graduate student had shifted, been complicated, challenged or reinforced.

I’ve tried to be honest with and truthful about my experiences, even as I’ve realized that this project has increasingly becoming a way for me to justify and value the work that I’ve been doing and that (I feel) has been undervalued or ignored by others. I’m not sure that I’ve always succeeded in being honest, but I have found the process of writing (and collecting) these various accounts of my student life to be useful and provocative and very necessary.

II. Explaining the Title

Over the past 15 or so years, I’ve requested my student transcripts many times for graduate school applications and my academic job portfolio. An official transcript, complete with an authorized seal from the institution on the back of the envelope, is expensive. And not always required for the first round of the application process. So, at some point, I acquired an unofficial copy. When a school needed my transcript, I’d send out a pdf of my unofficial copy instead of spending $5-10 (each) on a fancy, official version.

At the top of my unofficial Claremont School of Theology transcript is a stamp that states:

When I was thinking about what to call my intellectual history writing project, I played around with various titles, but none of them seemed quite right. Then, one day, while I was looking through a folder filled with old job application materials, I spotted this transcript and the “unofficial” statement stamped at the top. Yes, this was it, I thought. A great title for my project! Unofficial Student Transcript.

The more I’ve thought about it, the more I like this as my title. My intellectual history project is a record of my student work within the academy, from the earliest days of being a student in school all the way through to my explorations of and experiments with how to continue learning and engaging as a student while being the teacher. I’m including documents from school days, like report cards, lists of courses taken and taught, evaluations from professors, syllabi from past courses, copies of my doctoral exams, research and teaching statements and academic cover letters. In many ways, this project functions as proof, much like a transcript, of my time in school and my sustained engagement with key ideas and concepts in my chosen fields of study. Documenting my time as a student, which represents the majority of my life thus far (33 out of 38 years!), is important to me. I want to remember it and take it seriously and the process of reflecting on and documenting it allows me to do so.

But, the student transcript that I offer in the following accounts from my early years through Post-Ph.D work are not official. My perspectives and approaches to understanding the work that I did and the value of my education are not authorized by the academy or the institutions that I attended. In fact, my accounts frequently come into conflict with the “official” story about why and how one gets an education, earns a Ph.D and trains to be an academic intellectual. As will become apparent through my accounts, I have some real problems with the academy, or what I’m calling the academic industrial complex, and how it trained me to think, engage, teach and communicate my ideas to and with others.

My transcript is also not official because I’m not a real scholar, at least according to the hierarchy of Academics. I don’t even reside within academic spaces. I stepped out a year ago and am writing this in my uncertain position beside/s the academy. While the dismal job market was a factor for my current staate, I’m really in a self-imposed exile, where I’m trying to make sense of and take stock of where I stand (or want to stand) in relation to those academic structures and systems that shaped me into the troublemaking and troublestaying scholar that I’ve become.

In addition to lacking status (and a position) in the academy, my methods for thinking and writing are not officially sanctioned in the AIC. Much of my work for this project originated, in some form, on my writing and researching blog. While this work involves “serious” and deep engagement with “important” ideas, it was/is not usually recognized as such by academics because it’s not peer-reviewed or published in a top-tier journal or through a big-name publishing company. It also isn’t recognized because my aim was not to produce the newest, most cutting-edge theory that would ensure my status as a big-time fancy academic (BFTA), but to communicate and connect with a wide range of folks in my life that reside inside, outside and beside the academy.

As I compose this introduction, I’m starting to see that my assessment of the academic industrial complex might not be totally fair. I’m sounding angry and a little bitter. And maybe I am. I’ve devoted a huge chunk of my life to the academy. I was (and continue to be) passionate about learning, engaging with and deeply reflecting on interesting, provocative and world-shifting ideas. And I’m very disappointed with what the academy has done to that passion and how it’s trained me to be a scholar who feels compelled to spout jargon and reference countless theories every time I have a conversation.

My lack of fairness is another reason my student transcript is not official. It doesn’t offer objective, always factual truths. It’s biased, subjective and filtered through my current perspective as someone who is struggling to negotiate opposing forces and feelings. On one hand, I have an appreciation for the theories and ideas and training that my student years provided me. And I have many fond memories of being a student. But, on the other hand, I’m angry and frustrated about the current state of the academy and the ways in which it exploits students and teachers. And I’m sad about my loss of passion for being an educator.

Finally, my student transcript is not official because the accounts I’m providing in it are intended to unsettle, call into question and trouble any inclinations I have (and, believe me, I do) for offering up neat and tidy stories about my life as a student. I don’t want to offer up easy resolutions or moments of redemption; I want to play with and maintain the tensions and conflicted feelings and understandings in my accounts. My troubling intentions, which sometimes work and sometimes don’t, make me an unreliable and untrustworthy narrator whose accounts should never be official. And, I must add, I wouldn’t want them to be. I like being unofficial and inhabiting the spaces that that unofficial status makes room for. Continue reading Unofficial Student Transcript