For the past year or so, I’ve gotten in the habit of getting up at 6:15 AM, before anyone else in my house is awake. I make my extra strong coffee and sit on the couch, scrolling through my facebook and twitter feeds. Usually I’m looking for something that sparks my curiosity and inspires me to get into a critically reflective (troubling/troubled) space. Somedays I don’t find anything. But usually, there’s at least one item to read, watch or listen to. Today, on my first day back from winter break, I found two things. I’ve decided to archive them here.

Barbara Ehrenreich. New York Times, Sunday Review. Ehrenreich is great. Over the years, I’ve really enjoyed her critiques of positive thinking. It’s difficult to pick out just a few passages from her brief essay to post here (it’s all good), but I was especially drawn to these two:

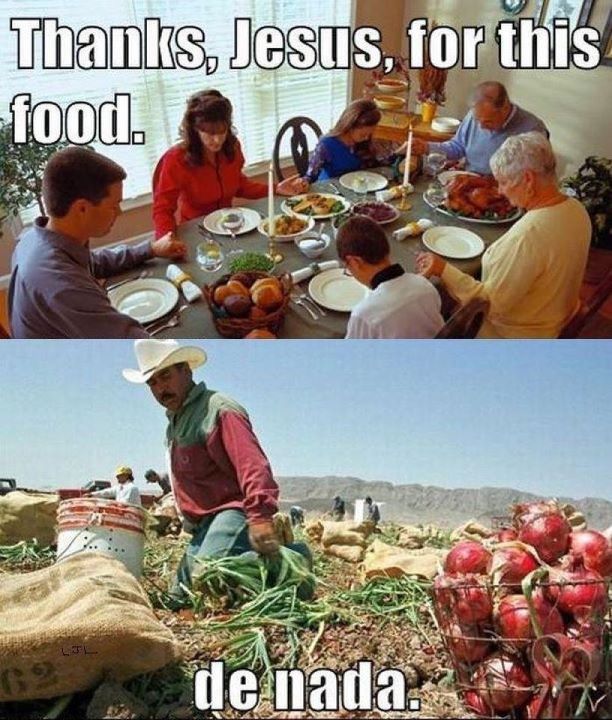

Gratitude to those who made your meal possible:

Yet there is a need for more gratitude, especially from those who have a roof over their heads and food on their table. Only it should be a more vigorous and inclusive sort of gratitude than what is being urged on us now. Who picked the lettuce in the fields, processed the standing rib roast, drove these products to the stores, stacked them on the supermarket shelves and, of course, prepared them and brought them to the table? Saying grace to an abstract God is an evasion; there are crowds, whole communities of actual people, many of them with aching backs and tenuous finances, who made the meal possible.

Not Gratitude but Solidarity:

The real challenge of gratitude lies in figuring out how to express our debt to them, whether through generous tips or, say, by supporting their demands for decent pay and better working conditions. But now we’re not talking about gratitude, we’re talking about a far more muscular impulse — and this is, to use the old-fashioned term, “solidarity” — which may involve getting up off the yoga mat.

Ehrenreich’s mention of debt reminds me of Eula Bliss and her discussion of White Debt in the NY Times last month.

Stephanie Danler. Paris Review.

There are two kinds of women: those who knit and those who unravel. I am a great unraveler. I can undo years of careful stitching in fifteen gluttonous minutes. It isn’t even a decision, really. Once I see the loose thread, I am undone. It’s over before I have even asked myself the question: Do I actually want to destroy this?

I don’t unravel in the same way as the author, but I like thinking about my practices of undisciplining and unlearning as forms of unraveling bad habits and toxic/unhealthy narratives about myself and the world.