Some days I look at my twitter feed and I don’t find anything that makes me curious or inspires me to ask questions and reflect. But, not today. I don’t know if it’s the 16 oz latte, my 2.5 mile jog at the YWCA, or the early snow that has my “little gray cells” working overtime, but I have a big list of items to think/reflect/trouble/write about on this snowy, cold Monday in November. At first, I was planning to write a series of blog entries on each topic, but I soon realized that that was too much. So instead, I’ve decided to create a post with just a few of the links, along with some reflections.

Some days I look at my twitter feed and I don’t find anything that makes me curious or inspires me to ask questions and reflect. But, not today. I don’t know if it’s the 16 oz latte, my 2.5 mile jog at the YWCA, or the early snow that has my “little gray cells” working overtime, but I have a big list of items to think/reflect/trouble/write about on this snowy, cold Monday in November. At first, I was planning to write a series of blog entries on each topic, but I soon realized that that was too much. So instead, I’ve decided to create a post with just a few of the links, along with some reflections.

Item One

Did Jezebel cross the line by ratting out teens for their racist tweets?

Background: Shortly after President Obama was re-elected last week, some twitter users began tweeting their highly racist reactions. And the data-mapping experts over at Floating Sheep tracked and mapped them. This tracking, particularly how the map made visible where certain clusters of racism tweets existed (i.e. Alabama and Mississippi), was a popular topic on twitter, facebook, blogs and online news sources. A few examples: Map Shows You Where Those Racists Tweeting After Obama Election Live (Colorlines), The Racist States of America (Daily Mail UK) and Twitters Racists React… (Jezebel).

According to Slate, Jezebel took their tracking of the story too far, by not only publicly shaming the twitter users, who were primarily teens, but by

reaching out to the tweeters’ schools to get the kids in trouble (and, presumably, to gin up page views). They then meticulously noted each administrator’s response. They also updated us, gleefully, on the status of the students’ twitter accounts: Which kids were embarrassed enough to delete them? Which ones offered half-assed excuses? Which ones doubled down on their racism?

Here’s Jezebel’s follow-up post, detailing their efforts to contact the tweeters’ school officials in order to hold the tweeters accountable and in the hopes that the officials could “educate them on racial sensitivity.” In their critique of Jezebel’s actions, Slate author Katy Waldman, argues that a major media outlet like Jezebel is not the appropriate venue for meting out discipline. It not only punishes these “stupid kids” too severely for their lack of judgment (evidence of their mistake and the resultant shaming will exist for years online), but is more likely to piss them off and shut them down, then encourage them to be educated and accountable for their tweets. Here’s the closing line of the brief article:

Morrissey writes: “We contacted their school’s administrators with the hope that, if their educators were made aware of their students’ ignorance, perhaps they could teach them about racial sensitivity.” Perhaps. More likely, as my colleague put it in an email: “It probably won’t make them less racist if they’re bitter forever.”

Initially, I felt that the Slate article was a bit too harsh but now I’m not so sure. These tweets are abhorrent and the users who tweeted them should be held accountable, but these teens are minors and represent only a handful of individuals who contribute to (but have not created) the larger systems of structural racism in this country. To shame only these kids (or primarily these kids) enables us to ignore/suppress the larger structures of racism and to fail to consider all of the ways that racist attitudes continue to exist within this country. It’s much easier to focus our attention on a few “stupid kids,” then to face the reality that, as Colorlines’ author Jorge Rivas writes: “racists are everywhere.”

This Slate article raised some interesting questions for me:

1. How should we hold users, especially teen users, accountable for their tweets?

2. What sorts of resources are available for educators, parents, community members for learning how to be more accountable and responsible online?

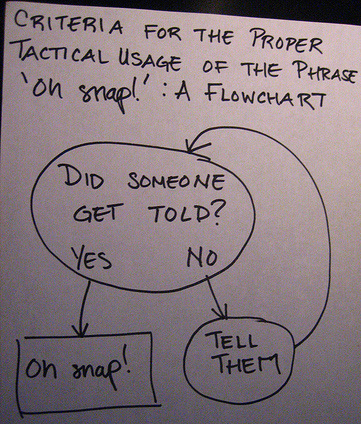

3. After further reviewing comments from the Jezebel post, I came across this thread in which commenters discuss how they’re contacting school officials. One user refers to these actions as internet vigilantism.

Is “internet vigilantism” an effective tool for holding individuals accountable?

Item two

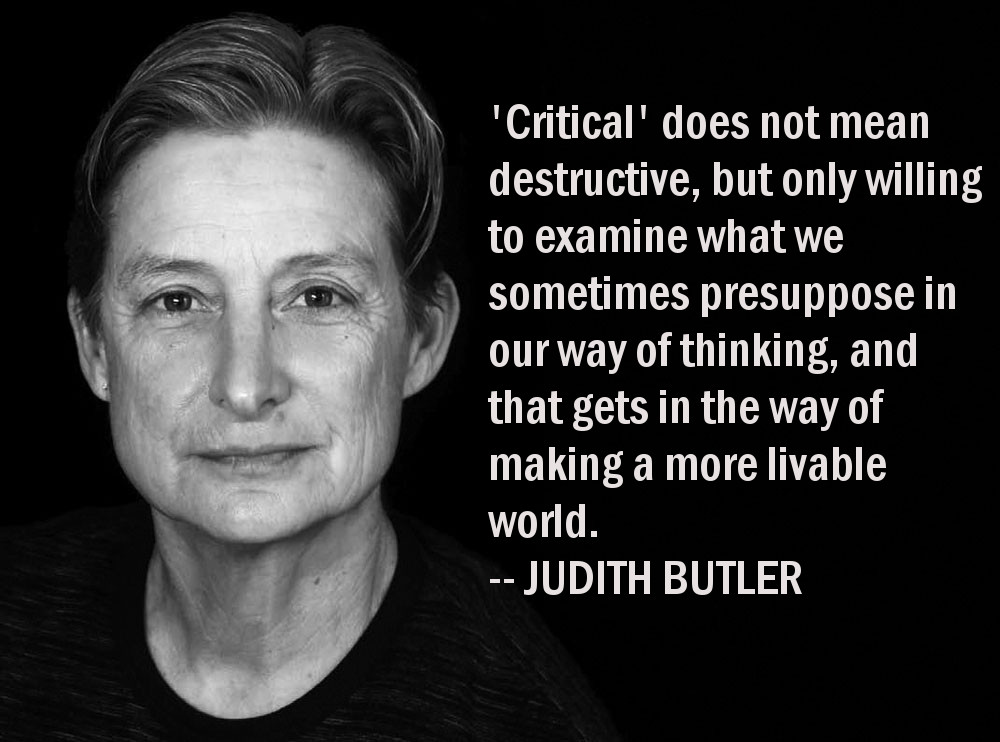

Two Random Encounters with Judith Butler

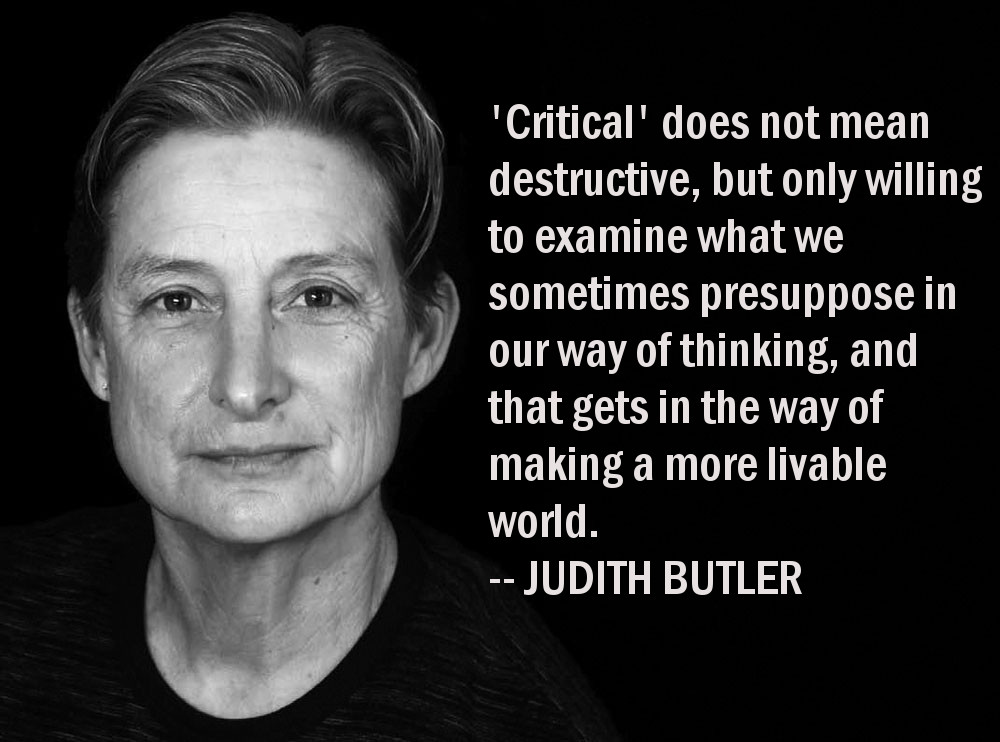

1. I found an excellent quotation (from a recent interview) on a great post by Michael D Dwyer about teaching pop culture. His use of this quote comes in a section of his post in which he discusses how we can be both critic and consumer of pop culture (this was a big focus in my pop culture class from 2007).

2. I learned about an advice book that Butler contributed to via this Brain Pickings post. This find is one of the reasons why, even as I am wary of Brain Pickings, I still follow them on twitter. Butler contributes an essay on “Doubting Love,” in the 2007 advice book, Take My Advice: Letters to the Next Generation. Looking forward to reading this one; I’ve already requested it from the Minneapolis Public Library! I’d like to think about this advice book in relation to my other research on the self-help industry.

Item Three

Well, I’m quickly running out of time (less than a half an hour before I must pick up RJP from school), so I can’t write much more. Why am I not surprised?! Here’s a In Media Res curated series on The Second Lives of Home Movies that I want to read and reflect on…and put beside my work on home tours.

Bonus Item

Inspired by the snow this morning (and by my desire to experiment with my new iMovie app), I created a digital moment: Minnesota Weather. I plan hope to write more about my thoughts and experiments with the iMovie app soon. For now, here’s my digital moment + my description of the story):

minnesota weather: a digital moment from Undisciplined on Vimeo.

I’ve lived in Minneapolis for the past 9 years (plus 4 years in St, Peter, MN for college and 18 months in Minneapolis in the late 90s) and I still haven’t gotten used to the unpredictable weather. Minnesotans always say, “Don’t like the weather? Just wait 10 minutes.” I was reminded of this phrase when I woke up this morning. Just last week it was sunny, with beautiful leaves on the trees. And, just two days ago, it was in the upper 60s. But, when I looked out my window this morning, around 7 AM, there was snow on the ground. This example of pure Minnesota seemed worthy of a digital moment.