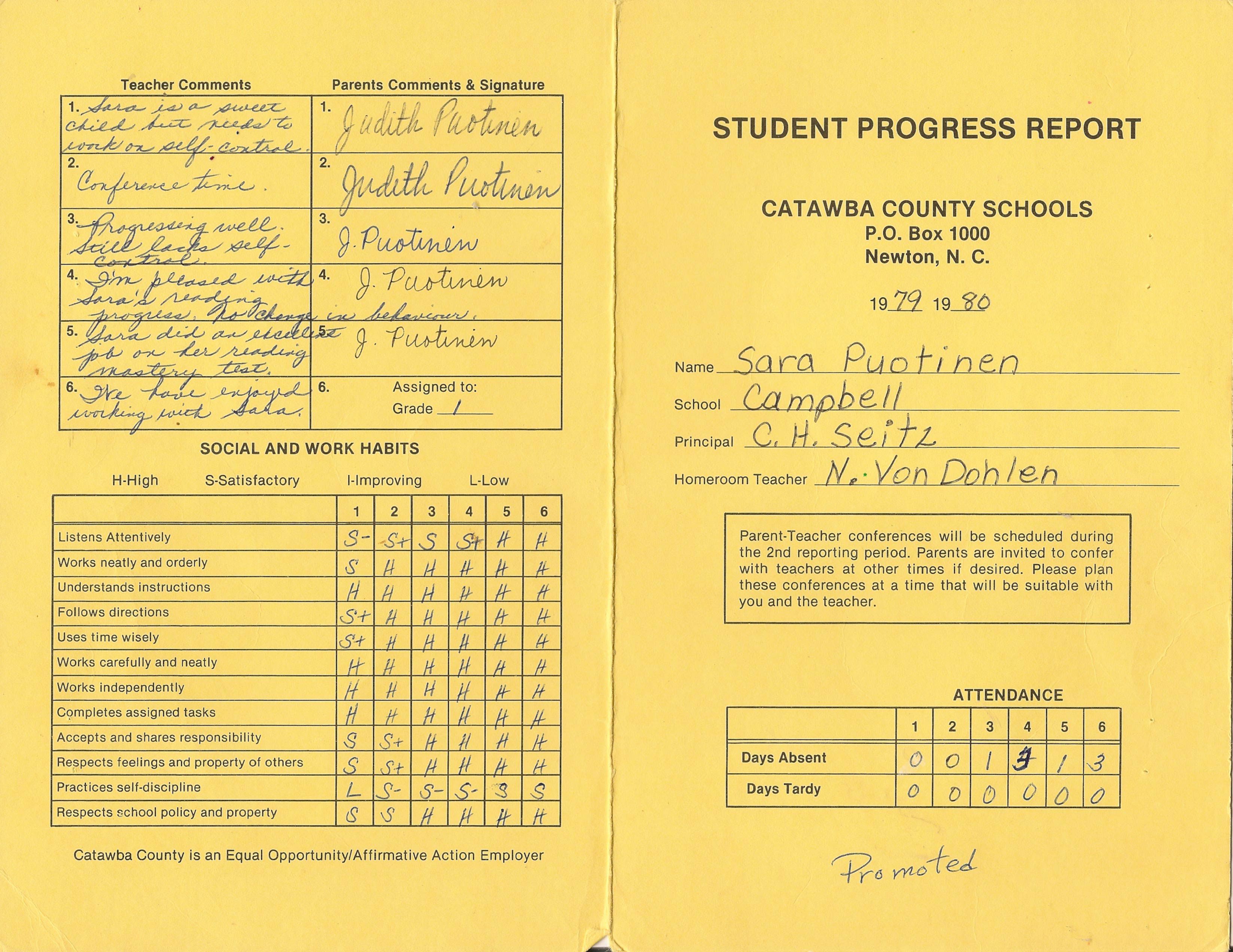

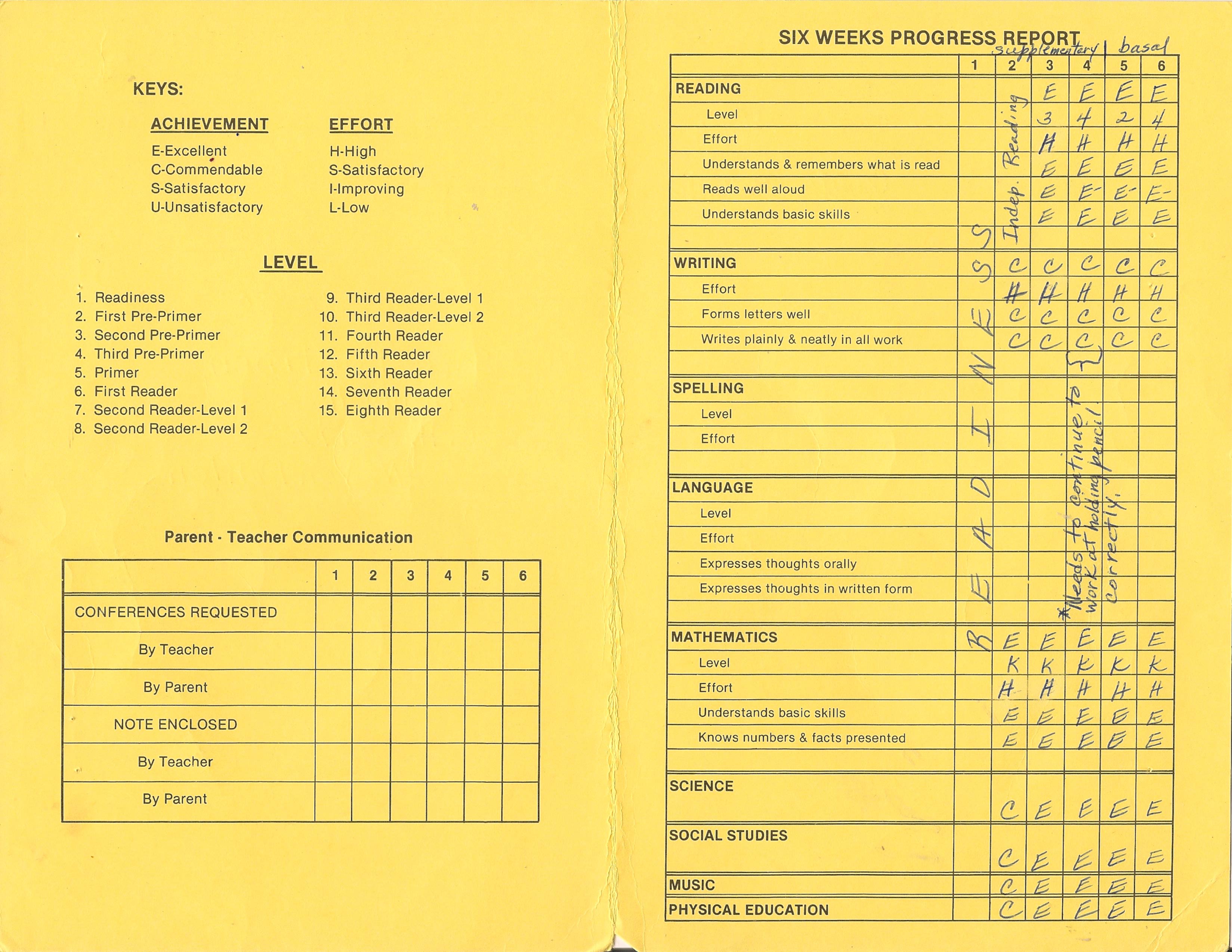

According to Harold Gardner in The Disciplined Mind, written in 1999:

In contrast to the naive student or the information-crammed but still ignorant adult, an expert is a person who really does think differently about his or her speciality. The expert has successfully achieved the desire set of engravings. Expertise generally arises as a result of several years of sustained work within a domain, discipline or craft, often courtesy of a traditional apprenticeship. Part of that training involves the elimination of habits and concepts that, however attractive to the native person, are actually inimical to the skilled practice of a discipline or craft. And the remaining part of that training involves the construction of habits and concepts that reflect the best contemporary thinking and practices of the domain (123).

In an updated version of his theories on discipline, truth, beauty and goodness, Truth, Beauty and Goodness Reframed, published in 2012, he writes:

In the search for truth, our greatest allies are the scholarly disciplines and the professional crafts—in short, areas of expertise that have developed and deepened over the centuries. Each discipline each craft explores a different sphere of reality and each attempts to establish truths—the truths of knowledge, the truths of practice (23).

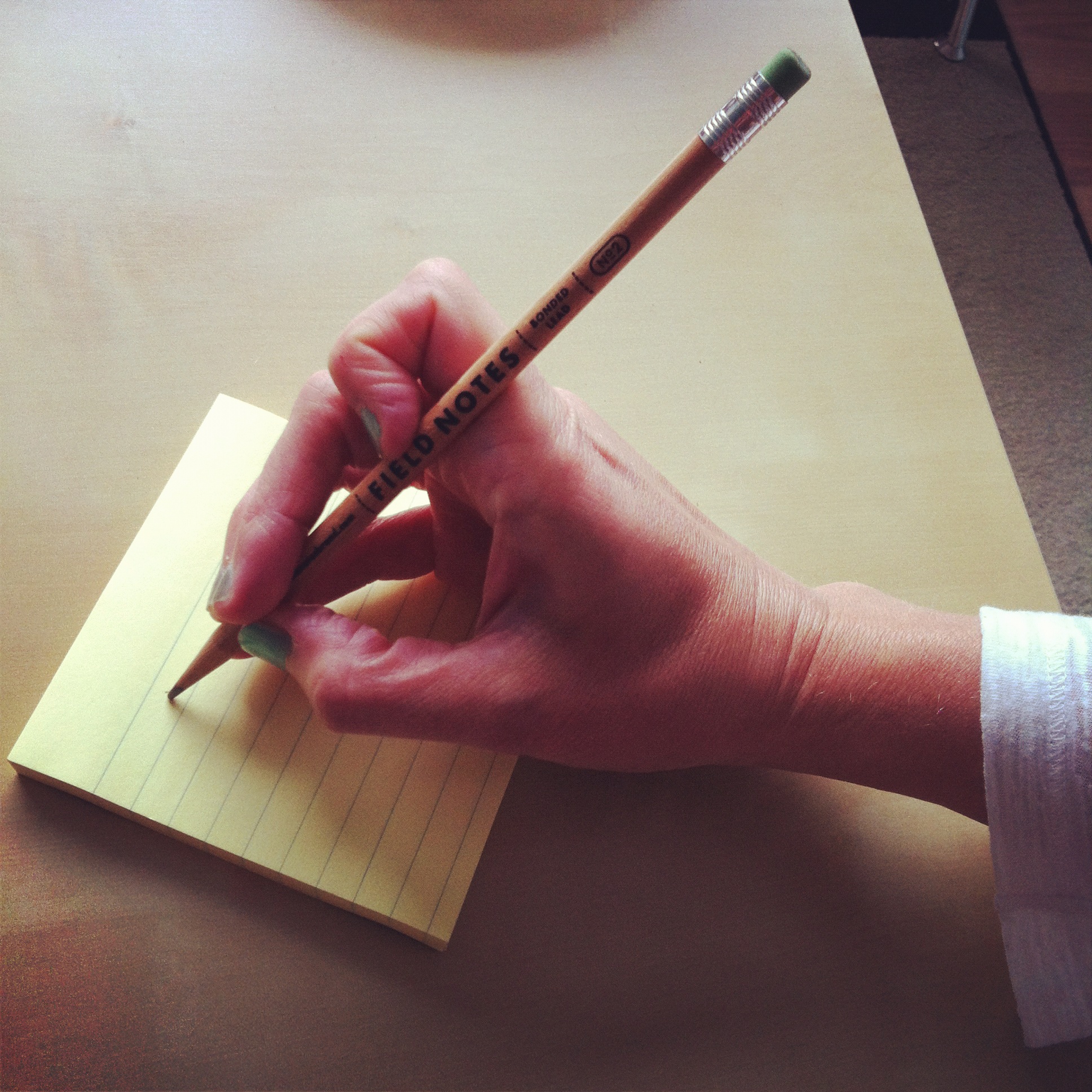

I haven’t been able to read through Gardner’s work that carefully yet, but in starting to ponder the value of disciplines and being disciplined, I’m troubled. While I appreciate the need for sustained attention to a topic and for cultivating a certain set of skills, I’m less convinced that this sort of education is best achieved by mastering an academic discipline or by working solely within academic disciplinary frameworks. Additionally, I’m skeptical of the appeal to a set of “experts” as the masters of a particular set of truths, especially when who can claim or be counted as an expert is so limited (and is so frequently biased against certain forms of knowledge).

Besides

Aaron Swartz

As I reflect on these ideas about disciplines and being disciplined today, on January 13, 2013, Gardner’s books aren’t the only things I’m thinking about. This morning, I also read Aaron Swartz’s speech, How to Get a Job Like Mine. Tweets about his tragic suicide on Friday have taken over my twitter feed. In the midst of tweets honoring his contributions and tweets raging against what (and who) caused his death, I found a link to a 2007 talk that he gave at a computer conference. I want to put this talk and his advice, as a mentor, but not an expert, on how to have a energizing, yet stressful job like his, beside Gardner’s theories. Here’s his pithy advice:

- Be curious. Read widely. Try new things. I think a lot of what people call intelligence just boils down to curiosity.

- Say yes to everything. I have a lot of trouble saying no, to an pathological degree — whether to projects or to interviews or to friends. As a result, I attempt a lot and even if most of it fails, I’ve still done something.

- Assume nobody else has any idea what they’re doing either. A lot of people refuse to try something because they feel they don’t know enough about it or they assume other people must have already tried everything they could have thought of. Well, few people really have any idea how to do things right and even fewer are to try new things, so usually if you give your best shot at something you’ll do pretty well.

I want to think some more about Swartz’s advice, and his activist efforts to challenge JSTOR so as to ensure that more people had access to information and ideas produced within the academy. When Gardner argues for the need to master a discipline and learn from experts, who has access to that knowledge (and who doesn’t)?

Digital Media Learning: Everyone

Also today, I watched a Digital Media Learning Connected Learning Video:

opening / ‘the march of the formal educational curriculum is at a very different pace from how kids interests develop.’

closing / ‘a sense of fulfillment, belonging and purpose are possibly more important than the knowledge being cultivated.‘

Chrome: Expanding Access and Who Counts as an Expert

And, while I was watching the very exciting Atlanta Falcons vs. Seattle Seahawks football game, I saw this commercial for Chrome:

Where do experts come from?

What sort of knowledge do they offer?

How does the internet complicate how and where we learn and/or gain expertise?

As I work through my own troubled reactions to the need for discipline (which include my questioning of my continued embracing of being undisciplined and whether or not you need to first be disciplined in order to be undisciplined), I want to put all of these ideas beside each other.