In case you missed it (ha!), the talk on twitter two weeks ago was all about Invisible Children’s Kony2012 campaign. The hashtag #stopkony was trending like crazy and everyone (okay, not everyone) was tweeting about how you should watch the video (which was almost 30 minutes long) on youtube if you cared about “children in Africa.”

The initial buzz focused on how amazingly successful this campaign seemed to be and how it was inspiring so many people to care about an issue and people that they so often ignored. However, I was pleased to see how quickly writers/critics/scholars/activists stepped in and began raising important critical questions about the problems with this campaign: its focus on Uganda, it’s plan for making Kony visible, it’s paternalistic/white savior approach. As a side note, I’ve been noticing lately that there seems to be more visibility for critical voices on the web (or, am I just more tuned in to it?) that are challenging viral media and quick/easy/short-sighted solutions to huge problems. In this post, I don’t want to add to the insightful critiques that many have offered (critiques that keep coming as the topic gets increasingly more bizarre with Invisible Children’s founder, Jason Russell, being detained by police for erratic behavior and public masturbation last week). Instead, I want to use this post as a space for archiving a few of the blog posts/articles that are particularly interesting for me and my thinking about twitter and how it can be ab/used for generating empathy and inspiring people to care.

Here they are (in no particular order):

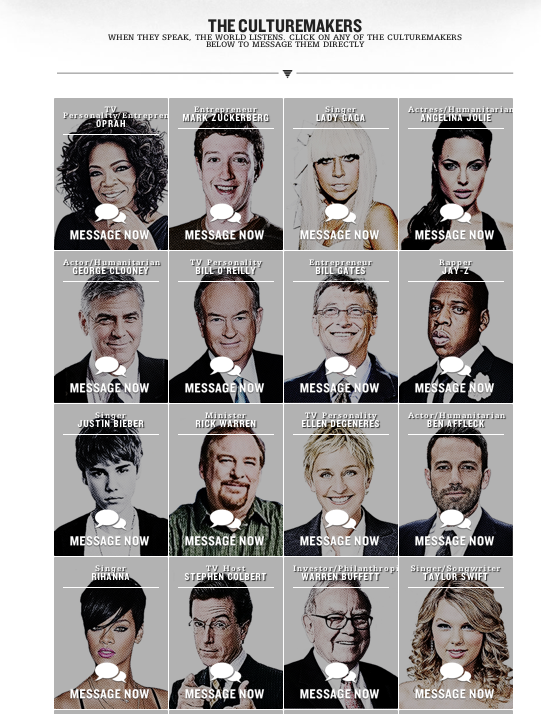

1: [Data viz] KONY2012: See How Invisible Networks Helped a Campaign Capture the World’s Attention

This post looks at the data to understand how this viral campaign went viral (hint: it didn’t just “happen”) by targeting specific, highly influential celebrities (like Ryan Seacreast…ugh) and by tapping into a network of motivated, concerned Christian youth:

This movement did not emerge from the big cities, but rather small-medium sized cities across the Unites States. It is heavily supported by Christian youth, many of whom post Biblical psalms as their profile bios. Below is a wordle tagcloud highlighting the most common words that appear in their user bios. We easily identify prominent words such as Jesus, God, Christ, University and Student.

2: Why We Should Take Heart from the Backlash Against the Kony Campaign

This article offers a positive spin on how critics were able to quickly and effectively (at least to some extent) challenge the campaign.

It’s online where the Tumblr posts, tweets, and videos from more critical voices can add up and become a wave of dissent. Yes, the Internet may spread bad ideas, but it also opens up new avenues for good ones, dissenting ones…

It also cautions against judging the spreaders of this campaign (mostly Christian youth) too harshly. Hmmm….I want to think about this some more…

In the end, the people (teenagers) who spread this video were motivated by a desire to help, no matter how misguided and problematic the organization behind it. It is easy to be cynical, but the desire to do good by your fellow person is widespread. The video’s virality demonstrates that. May the Kony 2012 backlash result in informing that desire, so that it is humbler, smarter, and can recognize a no-good campaign the next time one comes around.

3: Unpacking Kony 2012

This post provides an excellent and insightful overview. He asks some really important questions about social media and activism, like: Can we advocate without oversimplifying? [good link in post to a discussion of Russell’s video as a “story of self”]

In his conclusion, he raises a ton of questions that could have me thinking/reflecting/ruminating for days. I must return to these question in future reflections:

I’m starting to wonder if this is a fundamental limit to attention-based advocacy. If we need simple narratives so people can amplify and spread them, are we forced to engage only with the simplest of problems? Or to propose only the simplest of solutions?

As someone who believes that the ability to create and share media is an important form of power, the Invisible Children story presents a difficult paradox. If we want people to pay attention to the issues we care about, do we need to oversimplify them? And if we do, do our simplistic framings do more unintentional harm than intentional good? Or is the wave of pushback against this campaign from Invisible Children evidence that we’re learning to read and write complex narratives online, and that a college student with doubts about a campaign’s value and validity can find an audience? Will Invisible Children’s campaign continue unchanged, or will it engage with critics and design a more complex and nuanced response.

4: Kony 2012’s Success Shows There’s Big Money Attached to White Saviors

Building on Zuckerman’s questions about the oversimplification of narratives and issues, this post asks:

But the campaign’s visibility is forcing to the surface some uneasy questions about race, political organizing, and the Internet. Namely: Must nuanced political issues be narrowed down to their simplest forms in order for the public to digest them? Can that issue work without perpetuating deeply problematic caricatures about race? And what, in the long run, does it mean to “win”?

Within days, Ugandan journalist Rosebell Kagumire rose to the top of a chorus of African voices criticizing the campaign.

“It simplifies the story of millions of people in northern Uganda and makes out a narrative that is often hard about Africa, about how hopeless people are in times of conflict,” Kagumire said of the Kony 2012 video. “If you are showing me as voiceless, as hopeless, you have no space telling my story, you shouldn’t be telling my story.”

5: The Road to Hell is Paved with Viral Videos

Here’s an explanation of the title of this article/post:

As a film, as history, and as policy analysis, there is little to be said forKony 2012 except that its star and narrator, Jason Russell, the head of Invisible Children, and his colleagues seem to have their hearts in the right place. But this do-good spirit is suffused with an almost boastful naiveté and, more culpably, an American middle-class provincialism that illustrates beautifully the continuing relevance of the old adage about the road to hell being paved with good intentions.

on paternalistic care:

if the narrative structure of Kony 2012 is reminiscent of anything, it is of a tried and true paternalism that the missionaries milked for all it was worth when they returned to the metropole from the outposts of the British and French empires in which they were working. Rather than trying to inspire, inform, and mobilize kids through the efficiencies of Facebook to care about faraway tragedies and needs, the missionaries had to content themselves with the largely retail work of mobilizing the faithful.

Later on in the article, the author suggests that the naive, feel-good, unthinking approach to inciting people to care is “childlike.” He describes it as: “cheap techno-utopianism that conflates the entirely admirable wish for a better world with the belief that knowing how to move toward it is a simple matter, requiring more determination and goodwill than knowledge.” While I appreciate his critique here of the problems with oversimplification, I don’t fully agree with his critique/dismissal of kids as critical thinkers/agents/resistors. Many kids are troublemakers who recognize that easy narratives exist and that refuse to uncritically accept the truths that are fed to them. And, many kids, especially teenagers, not only have the capacity for but practice a critical ethics of care. Maybe instead of describing a lack of critical thinking and ethical complexity as childlike, he could have used Cornel West’s understanding of “childish” (which I wrote about at the end of this post):

I want to come back to your point about immaturity because I want to make a distinction between “childish” and “childlike.” You see, the blues and jazz are childlike, the sense of awe and wonder and the mystery and perplexity of things. “Childish” is immature.

6: The White Savior Industrial Complex

The author offers his response to Kony2012 through a series of tweets and then discusses how those tweets have resonated with many audiences. Here are few of the tweets:

2- The white savior supports brutal policies in the morning, founds charities in the afternoon, and receives awards in the evening.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) March 8, 2012

3- The banality of evil transmutes into the banality of sentimentality. The world is nothing but a problem to be solved by enthusiasm.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) March 8, 2012

4- This world exists simply to satisfy the needs—including, importantly, the sentimental needs—of white people and Oprah.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) March 8, 2012

5- The White Savior Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) March 8, 2012

This article provides an excellent critical discussion of care, like on how the sentimental white savior only sees need (e.g. hungry mouths), but sees no need to reason out the need for need or how sentimental caring and the need to “make a difference” enables us to ignore larger structures of power:

Let us begin our activism right here: with the money-driven villainy at the heart of American foreign policy. To do this would be to give up the illusion that the sentimental need to “make a difference” trumps all other considerations. What innocent heroes don’t always understand is that they play a useful role for people who have much more cynical motives. The White Savior Industrial Complex is a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. We can participate in the economic destruction of Haiti over long years, but when the earthquake strikes it feels good to send $10 each to the rescue fund. I have no opposition, in principle, to such donations (I frequently make them myself), but we must do such things only with awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.

Yikes! I intended this post to be brief and to only take a few minutes to write. Ha! Oh well, it was very helpful for me to spend the time reading through these posts and thinking (again) about care on/through/with twitter.