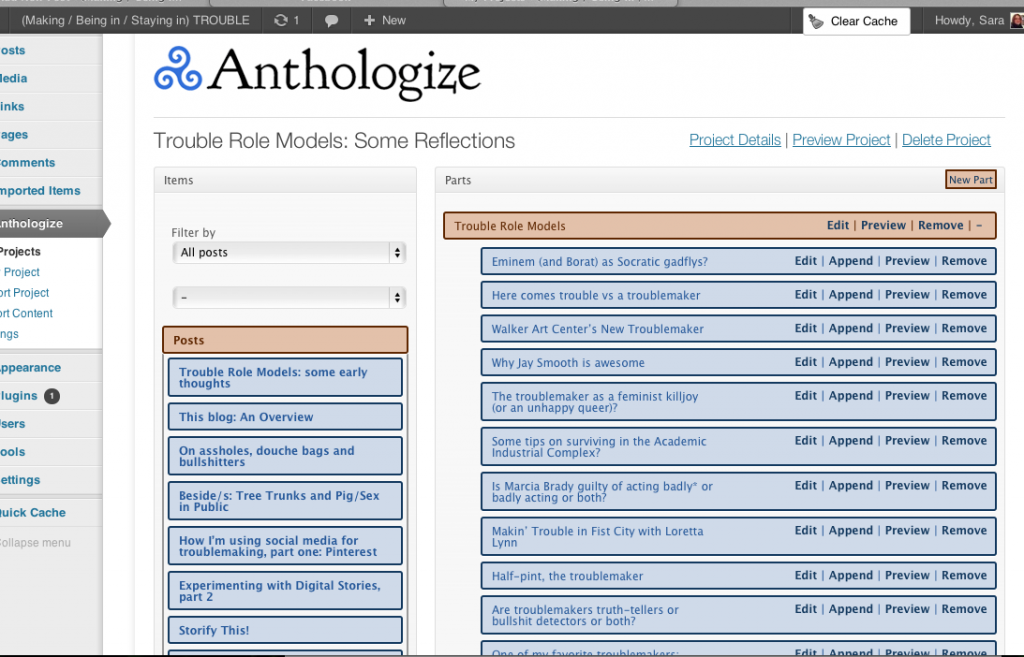

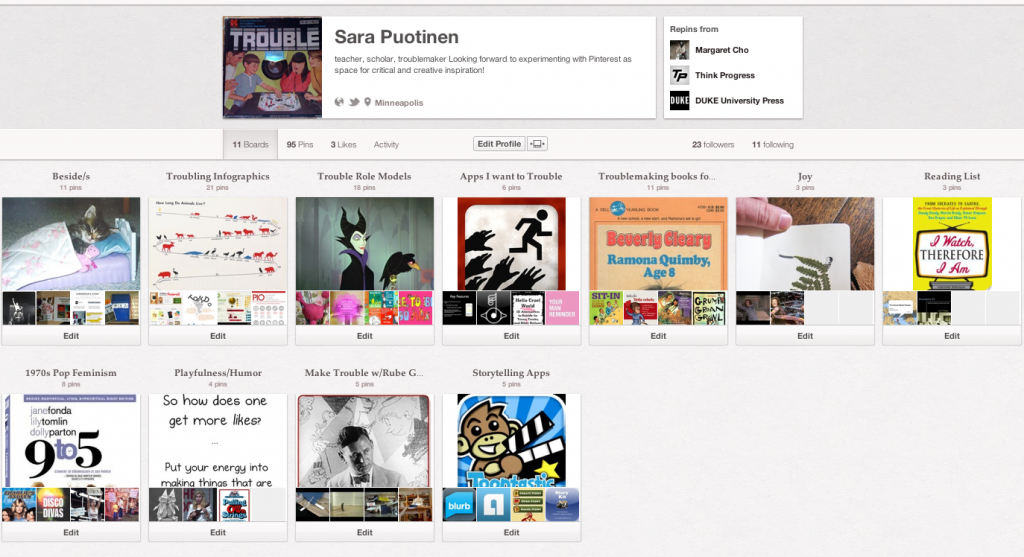

Right now, I’m experimenting with converting parts of this blog into a pdf with Anthologize. I’m not sure what I’ll ultimately do with it, but it seems like a helpful exercise in thinking through how to (finally) turn my reflections on/engagements with trouble into a more tangible product. Plus, after discussing how much I’ve written on my blog with STA on our podcast yesterday, I’m interested in finding out how many pages my 288+ posts equals.

I tried out anthologize about 2 years ago and wasn’t that impressed. Since then, they’ve updated it and I’ve found new ways that it might be useful. When I first got the idea for this project yesterday, it seemed like it would be pretty easy. All I had to do was drag my posts into different parts of my “book.” Ha! Today, as I become increasingly overwhelmed by the number of posts I have and by the various ways in which I might organize them, I realize that this project is not going to be easy. Useful? Probably. But easy? Definitely not. Oh well.

In order to not get too overwhelmed, I’ve decided to approach the project in chunks. Today’s chunk: Trouble Role Models.

As I skimmed through an entry in tribute to Mary Daly, I came across these lines:

In my dissertation, Feminist Ethics and the Project of Democracy, I argue that we urgently need feminist role models who aren’t saints, but are moral exemplars of the resisting spirit and who don’t necessarily show us how best to resist, but that resistance is always possible. These role models inspire us, providing us with the hope that we can transform oppressive institutions and live better lives. Their specific methods may not always be effective but, through their writing/teaching/activism/daily experiences, they encourage us to keep working and fighting and questioning.

I was inspired to return to my dissertation and my chapter on role models/radical subjectivities (which was written way back in 2004). Here are some things that I wrote about the importance of feminist role models:

Instead of developing new master narratives or searching for ways to guarantee success, feminists can find guidance and inspiration by looking to role models within their feminist communities. Through these role models, feminists can witness and engage with (oftentimes) living examples for how to survive and thrive within the dangerous and exhausting practice of democratic feminism. Feminist role models play an essential role in educating us on how to theorize about oppression, to practice our politics and to maintain our sanity. They also inspire us to keep going, even when we feel our actions might be hopeless.

In different ways, bell hooks, Bernice Johnson Reagon and Patricia Hill Collins all argue for the importance of feminist role models. In “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” bell hooks reflects on the value of “women and men who dare to create theory from the location of pain and struggle, who courageously expose wounds to give us their experience to teach and guide, as a means to chart new theoretical journeys” (74). She argues that is was because of these individuals and their willingness to risk theorizing about their own pain that she was able to begin (and continue on) with her own struggle against oppression in its many forms.

In “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century,” Bernice Johnson Reagon argues that, in order to keep their principles intact, feminists need to ensure the survival of those rare political individuals who refuse to reduce their political involvement to one issue, such as sexism or racism. These individuals not only keep up with and actively resist the ever-shifting ways in which oppression functions, but maintain their sanity as they do it. They “hold the key to turning the century with our principles and ideals intact. They can teach us how to cross cultures and not kill ourselves” (Reagon 1983, 363).

Finally, in Fighting Words, Patricia Hill Collins promotes the legacy of women and men who have dared to question and speak out against oppression or who were able to transform their rage into resistance. For Collins, this legacy includes those women, such as her mother, who lived on her block in her “African-American, working class Philadelphia neighborhood” (187). In spite of their unending struggles against a system that discouraged and actively tried to crush their dreams of a better life, these women were able to create and sustain hopeful visions of the future for themselves and their daughters by preaching self-reliance and independence. In so doing, they not only served as important role models for Collins; they also served as valuable sources of caring and encouragement, loving her “when no one else did and as no one could” (200).