Yesterday I posted this image. It was inspired by some theories/ideas that aim to resist the demand to have a positive attitude and just be happy. In this post, I want to offer a few passages from these theories as a way to engage with and make sense of the image and my motivations.

Yesterday I posted this image. It was inspired by some theories/ideas that aim to resist the demand to have a positive attitude and just be happy. In this post, I want to offer a few passages from these theories as a way to engage with and make sense of the image and my motivations.

SMILE OR DIE!

This phrase is a reference to Barbara Ehrenreich’s talk for RSA Animate (see transcript here). In this talk, she critiques “the ideology of positive thinking,” in which people are encouraged expected to have a positive attitude, act as if “there’s nothing wrong” and “just put a smiley face and get on with it.” The problem with this “delusion of positivity” is that it conceals or suppresses any dissent to or questioning of the larger structures that create conditions for our unhappiness. She says:

What could be cleverer as a way of quelling dissent than to tell people who are in some kind of trouble – poverty, unemployment etc – that it’s all their attitude, you know that that’s all that has to change, that they should just get with the programme, smile and no complaining. It’s a brilliant form of social control

So, the command to “smile or die!” is also a demand to not question, not worry and not think about why it might sometimes be good to not be happy. Now, Ehrenreich is not against joy or expressing/experiencing happiness. Instead, she’s against the larger ideology of positive thinking that demands that we suck it up, don’t complain, be cheerful and spread our good feelings to others.

KILLJOY

This idea of spreading good feelings and the ideology of positivity is one of the central themes in Sara Ahmed’s The Promise of Happiness. This book and Ahmed’s critique of the “happiness industry” are big inspirations for my image. I’ve written about the feminist killjoy in past posts. Here’s one of my favorite passages from Ahmed about the feminist killjoy:

Say, we are seated at the dinner table. Around this table, the family gathers, having polite conversations, where only certain things can be brought up. Someone says something you find problematic. You respond carefully, perhaps. You might be speaking quietly, but you are beginning to feel “wound up,”recognizing with frustration that you are being wound up by someone who is winding you up. Let us take seriously the figure of the feminist killjoy. Does the feminist kill other people’s joy by pointing out moments of sexism? Or does she expose the bad feelings that get hidden, displaced or negated under public signs of joy?

The killjoy is someone who refuses to just smile and be happy. Who is willing to be angry or worried or unhappy. Or who will always necessarily fail at being happy in the ways that are demanded of them (ways that usually include a narrow heteronormative/capitalist future and that require living within and therefore reinforcing certain norms).

I JUST WANT YOU TO BE HAPPY

Throughout the book, Ahmed reflects on a phrase that she repeatedly heard as a child: “I just want you to be happy.” She’s particularly interested in the “just want” of this phrase and its implications for thinking through how we understand our own happiness to be tied to others and their willingness to go along with what we imagine to be the right kind of happiness. In describing how this phrase gets uttered, she writes:

We can imagine the speaker giving up, stepping back, flinging up her arms, sighing. I just. The “just” is a qualifier of the want and announces a disagreement with what the other wants without making the disagreement explicit.

To exclaim that you “just want” someone to be happy is not simply to disagree with their approach; it is to claim that their approach will only lead to unhappiness and is therefore bad or not the “right” way to live. And it is to ignore or actively suppress their vision of happiness and joy all for the sake of their “true” happiness.

In my lecture notes from a Queering Desire course that I taught in 2010, I discuss what it means to be happy in the “right” way:

the very hope for happiness means we get directed in specific ways, as happiness is assumed to follow from some life choices and not others” (54).

What life choices are supposed to lead to happiness and which are not? Who gets to decide what leads to happiness and how are those decisions made?

The face of happiness, at least in this description, looks rather like the face of privilege. Rather than assuming happiness is simply found in “happy persons,” we can consider how claims to happiness make certain forms of personhood valuable (11).

Promoting happiness promotes certain ways of living (over others) and certain types of families (11).

“Ideas of happiness involve social as well as moral distinctions insofar as they rest on ideas of who is worthy as well as capable of being happy ‘in the right way'” (13).

A GOOD GIRL?

In May, I wrote about the problems with being a “good girl” in my post, On assholes, douche bags and bullshitters:

In “A Response to Lesbian Ethics,” Marilyn Frye (rightly) asks, “Why should one want to be good? Why, in particular, would a woman want to be good? (56). Her short answer: you shouldn’t. Her longer answer: The demand to be a good girl is intended to keep women in line, to pit them against each other–the “good girls/ladies” vs. “the bad/rebellious women,” and to prevent them from challenging dominant systems of power and privilege.

Be Nice?

This question is inspired by one of my posts from February about Pinterest’s etiquette rule: Be Nice. I wish I had taken a screen shot of the rules; Pinterest has since changed the rule to “be respectful” (which is a much better choice, IMHO). The idea of being nice has specific gendered connotations. I could write a lot about the whole “mean girl” phenomenon (which I taught in my Pop Culture Women course back in 2007…I’ll have to dig up those notes; I don’t think I posted them on that blog, which was my first one ever).

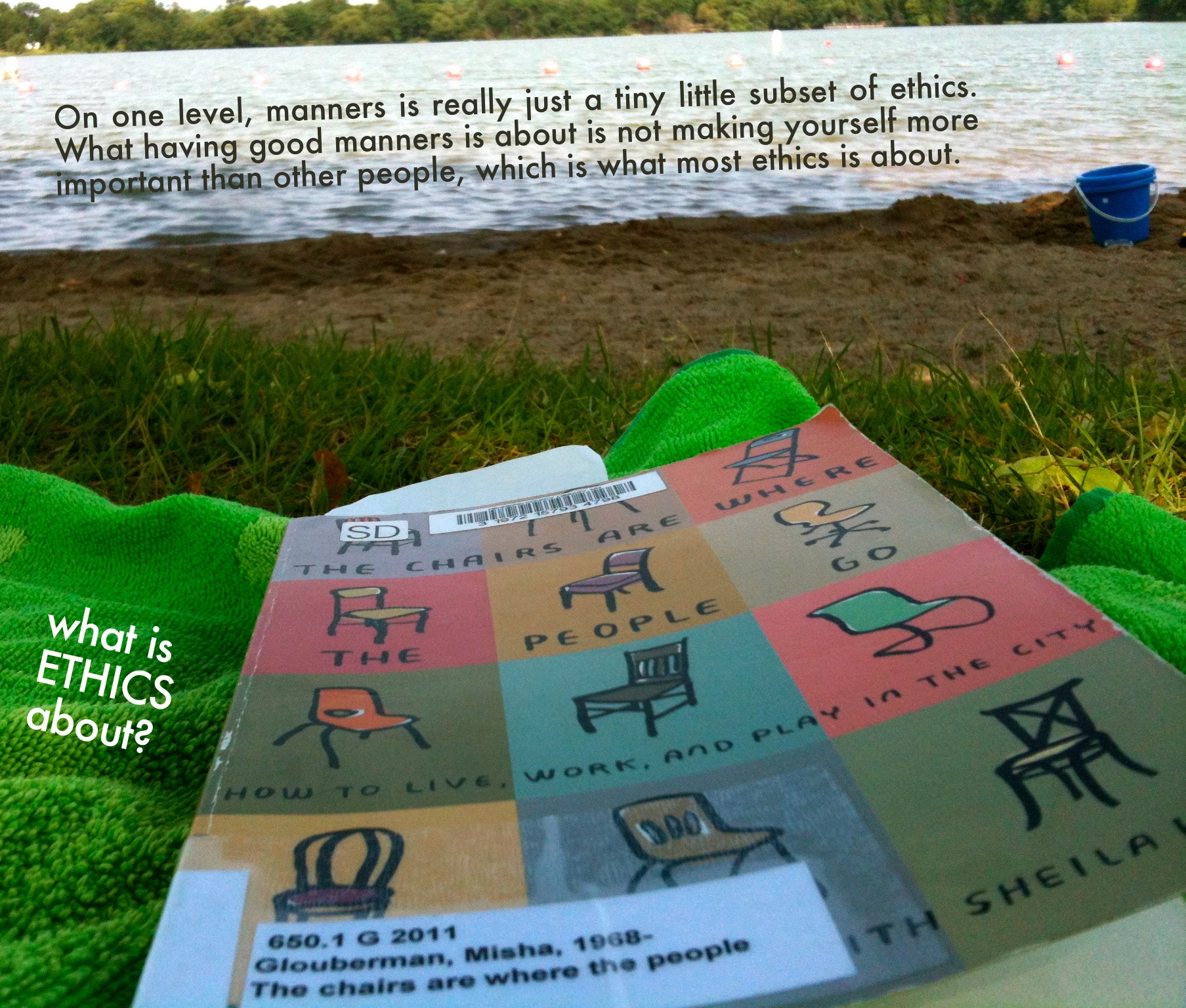

I think I should spend a lot more time writing about why “be nice!” troubles me. It has something to do with how little “being nice” seems to do with expressing care or concern or respect for others. I think it also has something to do with my disdain for etiquette, especially as it relates to “proper” discipline/behavior for girls/women. This disdain for etiquette and manners reminds me of a recent problematizer that I posted.

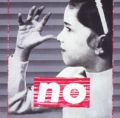

After doing a quick google search for Kruger, I realized that I had seen her work before–I think on a book cover? I like how she combines images with text, especially in this image to the left. I want to do so more research on her; I just requested a book from 2010 about her from the Minneapolis Public Library.

After doing a quick google search for Kruger, I realized that I had seen her work before–I think on a book cover? I like how she combines images with text, especially in this image to the left. I want to do so more research on her; I just requested a book from 2010 about her from the Minneapolis Public Library.