This morning, I finally finished watching the documentary, Paul Goodman Changed My Life. I had heard about it on twitter from one of my favorite tech-ed troublemakers, Audrey Watters (Hack Education). I’m not sure if I would call Goodman a troublemakng role model (hence the question mark in the title of this post), but I enjoyed learning about his life and his ideas. I want to think about it some more, but my initial hesitancy in identifying him as a role model involves how limited his caregiving for others, especially members of his own family, seemed to be. His version of troublemaking involved a relentless pursuit of the truth that lacked a consideration of the impact of that pursuit on specific, concrete others.

But, even if I don’t subscribe to his specific vision of making trouble, I enjoyed learning about it and Goodman’s life/writings.

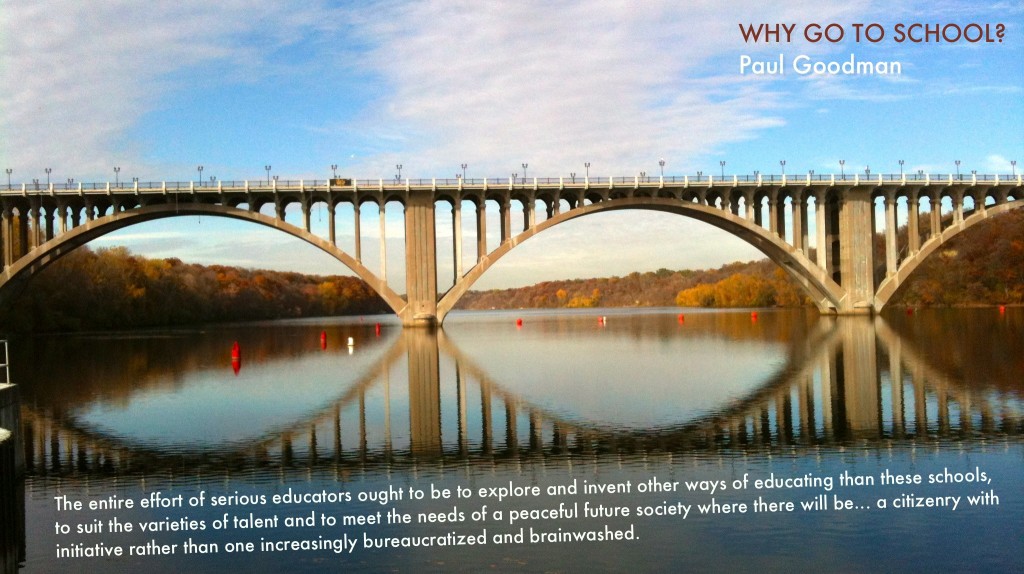

In her tweets about it, Audrey Watters also mentioned Goodman’s 1963 essay, “Why Go to School?” Goodman poses it as a challenge, not an explanation. He writes:

To sum up: all should be educated and at the public expense, but the idea that most should be educated in something like schools is a delusion and often a cruel hoax. Our present way is wasteful of wealth and human resources and destructive of young spirit.

The question, “Why go to school?” is one that resonates with me right now. Up until a few years ago, I never doubted that school was important, necessary and valuable. As a kid, I loved learning and going to school, even as I didn’t get along with several of my teachers. But, recently I have started to question the role of school as the primary location for learning. I don’t completely agree with Goodman’s claim that school is for many, “a delusion and often a cruel hoax.” However, I do wonder if schools, especially at the University/college level, can effectively prepare students to survive/flourish in the 21st century networked world. And I wonder what happens to other ways of knowing, learning and engaging when so much emphasis is placed on earning overpriced degrees.

One passage from Goodman’s essay inspired me to create a new Problematizer:

Here is the full passage:

The entire effort of serious educators ought to be to explore and invent other ways of educating than these schools, to suit the varieties of talent and to meet the needs of a peaceful future society where there will be emphasis on public goods rather than private gadgets, where there will be increasingly more employment in human services rather than mass-production, a community-centered leisure, an authentic rather than a mass-culture, and a citizenry with initiative rather than one increasingly bureaucratized and brainwashed.

As I read through this passage (and recall the rest of the essay), I am reluctant to fully agree. Yet, even as I reject Goodman’s extreme position, I’m find myself unable to offer convincing answers to his provocative question: Why go to school?