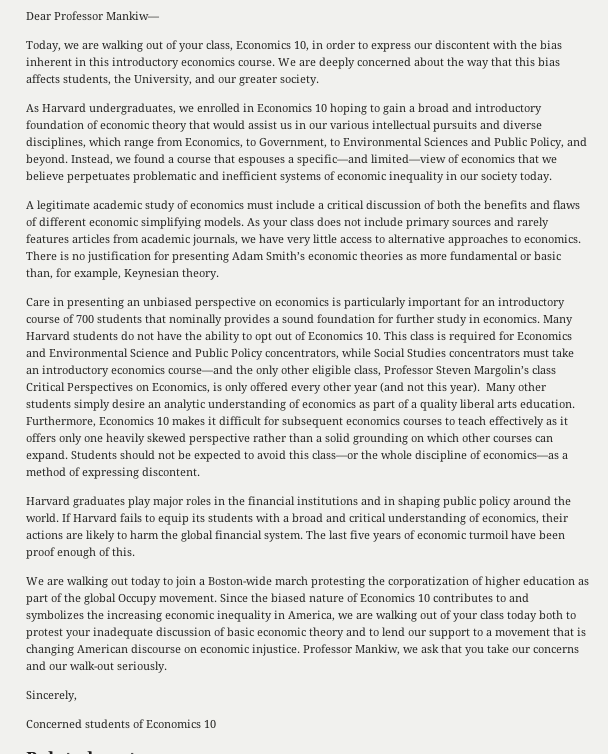

A few weeks ago, I came across this article: Did a Harvard Economics Class Cause the Financial Crisis? via @Good. 70 students in N. Gregory Mankiw’s Economics 10 class walked out in protest to Mankiw’s biased, ineffective, limited and dangerous teaching of introductory economics. In their open letter to Mankiw, they argue that

In brief, their reasons for protesting by walkout are:

- Information presented is biased, with no primary sources and no critical interrogation on limits

- Concepts, ideas, theories are narrow in scope and don’t allow for a broad foundation that can be used in future courses/work in different disciplines

- Failure to present students with proper tools for a future in which they will have power (privilege?) to influence major financial decisions

- Acting in solidarity with the Occupy movement

Care in presenting an unbiased perspective on economics is particularly important for an introductory course of 700 students that nominally provides a sound foundation for further study in economics.

Is it possible for any professor to offer an unbiased perspective? What sort of vision of the teacher is invoked with this myth of an all-knowing educator that can bestow honest, True (real) facts about what economics is or does? It sounds as if Professor Mankiw was particularly egregious in his failure to supplement his own bias with alternative perspectives, however all teachers present information in a biased way, based on their background (their interests, where they trained, where they were born/grew up, the cultural communities to which they belong, etc). And the solution to this bias is not to find a mythical teacher who can transcend their own positioning and perspective and present the facts or theories as they really are (whatever that means). Instead, the solution is to recognize that all knowledge is political/politicized and to develop strategies/tactics/skills for learning how to critically sift through various perspectives and determine which ones are most useful in understanding specific situations and problems. I’m sounding very Foucauldian right now. And that’s okay because I really appreciate what Foucault has to say about knowledge, power, the will to truth and the value of problematizing. One goal of an educator should be to provide students with these tools and tactics. Judging from the students’ letter, Professor Mankiw failed to offer any ways for students to learn how to decide between various theories; he didn’t provide primary sources or any justification for why some theories might be better or any admission of his own investments in certain theories over others. In protesting his failures (can we place this failure all on him? more on that in a minute), students shouldn’t argue for less bias, but more transparent teaching and more ways of learning how to negotiate between various ideas.

The idea that professors have certain investments and that ideas and theories are always shaped by who is using them and how is a central one in feminist pedagogy and is routinely taught in intro to gender and women’s studies courses. Can you see my bias here? I am a gender and women’s studies teacher, after all. Maybe instead of agitating against Professor Mankiw, students should be agitating for more feminist classes or feminist theory and feminist pedagogy that is integrated into intro to economics classes.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be an either/or situation. Students should agitate against professors who wield too much power even as they are agitating for a better education. But, does agitating against one bad apple really address the larger systemic problem? This question brings me to another aspect of the students’ letter (or, at least the way it was shared via twitter by Good with the question: Did a Harvard Economics Class Cause the Financial Crisis?), one that I will have to take up in a future post: In framing the problem of bad education as solely the result of the professor and/or his class, students are failing to address the various ways in which ineffective education, particularly in relation to economics and finances, is the result both of various practices on different levels of higher education (the Economics department at Harvard, Harvard University, Higher Education in the U.S) and of problematic pedagogical theories (like the banking method of education in which knowledge is deposited into the heads of passive students by the Expert Teacher). Why aren’t we having more of these conversations?