Last year during election season, there was a lot of talk about how John McCain was a maverick. But, what does that mean? What exactly is a maverick? And is it a type of troublemaker or something different altogether? According to dictionary.com, a maverick is “a lone dissenter, as an intellectual, an artist, or a politician, who takes an independent stand apart from his or her associates” and “one that refuses to abide by the dictates of or resists adherence to a group.”

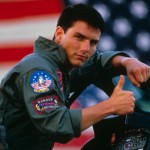

For John McCain being a maverick meant refusing to vote with his party on some important issues (at least this is his claim when he referred to himself as a maverick). In the case of ‘lil Tommy Cruise and his character in Top Gun–whose pilot name was Maverick–being a maverick meant rebelling by not only refusing to follow the rules but deliberately flaunting them so as to prove that they didn’t apply to him. The original meaning of maverick refers to a farmer in Texas named Samuel Maverick who didn’t brand his cattle. In this case, a maverick is: “an unbranded range animal, especially a calf that has become separated from its mother, traditionally considered the property of the first person who brands it.” This final meaning is fascinating to me. Could it be suggesting that a maverick is someone with no community of its own–and by extension no particular perspective or stance–whose allegiance is available to the first group to take them in or the highest bidder? Hmmmm–is that the kind of maverick that McCain is/was?

For John McCain being a maverick meant refusing to vote with his party on some important issues (at least this is his claim when he referred to himself as a maverick). In the case of ‘lil Tommy Cruise and his character in Top Gun–whose pilot name was Maverick–being a maverick meant rebelling by not only refusing to follow the rules but deliberately flaunting them so as to prove that they didn’t apply to him. The original meaning of maverick refers to a farmer in Texas named Samuel Maverick who didn’t brand his cattle. In this case, a maverick is: “an unbranded range animal, especially a calf that has become separated from its mother, traditionally considered the property of the first person who brands it.” This final meaning is fascinating to me. Could it be suggesting that a maverick is someone with no community of its own–and by extension no particular perspective or stance–whose allegiance is available to the first group to take them in or the highest bidder? Hmmmm–is that the kind of maverick that McCain is/was?

While there are some serious differences between these three descriptions, one thing remains the same: the maverick is a loner who doesn’t play nicely with his party (McCain) or follow the rules (‘lil Tommy Cruise) or really belong to any community or identity group (Samuel Maverick). The maverick is someone who acts alone and without others; who either rejects their community or doesn’t belong to one. It is this lack of belonging (and connection) that distinguishes the maverick from the troublemaker (at least, the troublemaker-as-virtuous-moral-agent).

Troublemakers do not act on their own. They act on behalf of and from within (even if from the fringes) a community or communities. They are selves-in-relation who are connected to others. And, in the words of J Butler, they are selves who are vulnerable, undone by, responsible for and to others. They are not loners. And their actions are not meant to isolate them from their communities.

In contrast, mavericks distance themselves from their communities; they act alone. A major point of their mavericky (thanks, Tina Fey!) behavior is to stake a claim as an individual who is not beholden to anyone. Hmm…The American Individual writ large. Yes, it makes sense that maverick, as a term, originates in the U.S. (and especially in Texas). It fits with the American ethos of wide open spaces, freedom as being left alone to do what you want to do (negative freedom), and individuality.