As I have mentioned before, I am experimenting with twitter this semester. In both of my classes (qued2010, femped2010), students are required to use it for various assignments and I am using it to communicate with class. Over the past month, several of my students in feminist pedagogies have live-tweeted class as a way to take notes for our discussion (I suggested it as an option for their note-taking assignment). Because I always like to try the experimental assignments that I suggest to my students (for lots of reasons, such as: I need to be willing to take the same risks that I expect my students to take and I want to make sure that the experiments that I come up with our actually doable), I decided to live-tweet my queering desire class yesterday. I’m really glad that I did. Here are some reflections on the process–I will include a transcript of my tweets after the jump).

Background: The class usually has 25+ students in attendance. It is an upper Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies course that is cross-listed as a mid-level GLBT Studies course. Blogging and tweeting are central to the class. Yesterday’s class was devoted to a discussion lead by a student group (part of their diablog assignment). We were talking about James Kincaid’s essay “Producing Erotic Children” in Curiouser. Because I was not responsible for leading class, I thought it was a good opportunity to try out live-tweeting. Instead of tweeting as the class administrator (qued2010), I tweeted as myself (undiscplined)

Some Thoughts:

1. I enjoyed it, but found it to be difficult. At first, I was a little scared. Documenting what students are saying in class is a big responsibility–what if I miss an important point or exclude student voices? It is also stressful because of the pressure to quickly post ideas in a very limited number of words.

2. It’s a helpful way to document the process of class discussion. There are all sorts of ways that I could imagine live-tweeting a class. You could tweet main points or offer up your own commentary on the discussion. You could limit the number of tweets in order to have time to (quickly) process the ideas being discussed. In my live-tweet I tried a different approach: my goal was to try and tweet as much of what was being said as I could. This meant I did a lot of tweets and that I didn’t spend much time trying to process/reflect on the discussion. The benefit of this approach is that I was able to document a lot of our discussion. The limitation of this approach is that I was not able to reflect (or engage) as much as I would have liked. I just counted the tweets: I did 52 for the hour of class. That’s a lot for me, especially considering that I had only done about 140 tweets total prior to class. This experience makes me want to tweet a lot more; it seems to be central to the twitter experience.

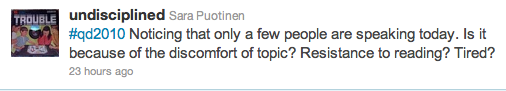

3. Does this encourage active listening? Yes and no. In my feminist pedagogies class the concept of active (sometimes non-judgmental) listening has come up a lot in our discussion. Berenice Fisher focuses on it in No Angel in the Classroom. AnaLouise Keating promotes it in Teaching Transformation. And Alejandra C. Elenes reflects on it in “Transformando Fronteras. Chicana Feminist Transformative Pedagogies.” I imagine active listening to involve attempting to really hear/understand what others are saying. It requires that we don’t rush to interject with our opinions or judgements, but that we sit back and let others speak. In most basic terms, it requires that we stop talking and start listening. Live-tweeting helps facilitate the “stop talking” part of active listening. When you are trying to document what everyone else is saying quickly and succinctly, you really don’t have time to offer up your own opinions (I suppose you could through your tweets–I didn’t). In my experience yesterday, I didn’t talk at all (okay, I think I talked once); I was too busy trying to type up what people are saying. So, because live-tweeting encouraged me to stop talking and to really listen to what students were saying so that I could accurately document it, I think live-tweeting encourages active listening. However, even as my live tweeting experience was encouraging me to listen closely, it wasn’t always encouraging me to listen deeply. As I mentioned above in #2, it is difficult to process and engage with class ideas when you are trying so hard to document those ideas–especially when students are so excited to talk that they are (almost) cutting each other off in order to express their thoughts on the reading/topic. At one point during the discussion I briefly thought, “Wow, I hope they don’t ask me to say anything; I can’t image what I could contribute to the discussion!” Also, I wasn’t really engaging with the students. In addition to not speaking, I didn’t offer up any non-verbal expressions either–no head-shaking affirmations or looks of confusion (or whatever other gestures I usually do–not sure what those are…I wonder if students would be willing to point them out?). As a result, I felt distanced from the class; even as I was listening, I wasn’t really there. Is that always a bad thing, I wonder? Maybe my role as the instructor should (at least sometimes) be to step back and let them talk and work through the issues. I want to keep thinking about this idea of active listening and how it works.

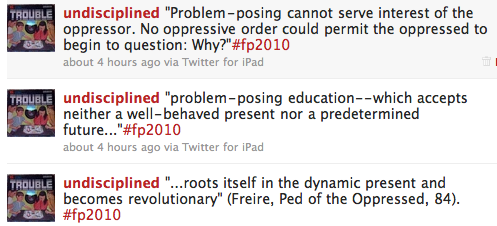

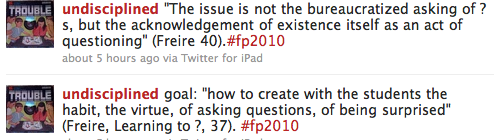

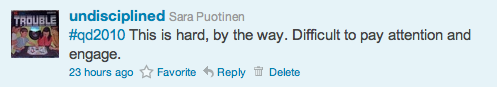

4. I want to experiment with how to interject more brief reflections on the class as I am tweeting. In the midst of tweeting about what was being said yesterday, I offered the following observations:

It might be helpful to add in more observations like these in the hopes that students will reply with thoughts (maybe during class–that could be hard–or after class, when they are reading through the live-tweet). As I wrote this last sentence, I thought of something else that I would like to reflect on as I think about how/when to use live-tweeting: Should I have the twitter feed projected on the screen as I am tweeting? Would that allow for more students to participate in the discussion as we are discussing? When does this become too distracting? Does it take away too much from the in-class engagement? Is it more productive to offer up the feed after class–to help continue the discussion online?

It might be helpful to add in more observations like these in the hopes that students will reply with thoughts (maybe during class–that could be hard–or after class, when they are reading through the live-tweet). As I wrote this last sentence, I thought of something else that I would like to reflect on as I think about how/when to use live-tweeting: Should I have the twitter feed projected on the screen as I am tweeting? Would that allow for more students to participate in the discussion as we are discussing? When does this become too distracting? Does it take away too much from the in-class engagement? Is it more productive to offer up the feed after class–to help continue the discussion online?

5. Some quick suggestions: I have spent almost an hour writing this post and I am running out of steam; it’s time to offer up some sort of conclusion. Here’s mine–in the form of a few brief tips/thoughts:

- I think more practice will allow for better live-tweeting. I need to get used to how to tweet, how to think quickly, and how to step back, while still engaging in the class.

- Next time, I want to have a list of everyone’s aliases with me. Ideally I want to do what my students in my fem ped class did: I want to put in the students twitter names (I want to “mention them”–with @) as I discuss their ideas. By mentioning them, I make it easier for them to read and respond to how I documented their words (they can reply to me with corrections, clarifications, reflections). I was only able to do this with a couple of students (I must admit that I did know more of the aliases, but felt overwhelmed by trying to type in some of the longer or more complicated ones. Here’s another good tip: encourage students to put in really short and easy to remember aliases!).

- Make sure to tell students that you are live-tweeting the class. I didn’t and I think it lead to some confusion and frustration with my lack of engagement in discussion. In the quick de-briefing at the end of class one student exclaimed, “I looked over and saw you on your computer all of the time and I thought, ‘She better not be on facebook while I’m trying to lead discussion!'”

Okay, I am sure that I have plenty more to write about this experiment, but I need to stop now. I plan to post parts of this entry on all of my different blogs, including my queering desire class (I’m writing it initially on my trouble blog). I hope that my students in queering desire will comment on this entry with their reactions to the experiment and their thoughts on what I did/didn’t document about discussion.

The entire twitter feed is after the jump. To read it in chronological order, go from top to bottom.