A few weeks ago I gave a presentation on my research, particularly as it relates to feminist media studies. Here is the first part of it. I plan to post the other parts in upcoming entries.

Staying in Trouble and Being Undisciplined,

or one way of doing feminist interdisciplinary work on and through digital media

I often tell students one effective way to understand what an author is trying to say is to explain their title. In that spirit I want to begin this presentation by explaining my title; in many ways, it speaks to who I am and what I aim to do as a scholar, critical thinker and educator-activist.

PART ONE: EXPLAINING THE TITLE

Staying in trouble and being undisciplined:

In much of my work, I am interested in exploring the ethical and political value of making and staying in trouble for feminist and queer projects and practices. This work is partly inspired by Judith Butler and her claim that “trouble is inevitable, the task how best to make it, what best way to be in it.” While I imagine troublemaking and troublestaying working in many different ways, I am particularly interested in how they can connect to a feminist curiosity about the world, a persistent desire to ask lots of questions (like “why?” and “at whose expense?”), and a refusal to uncritically accept ideas or practices as given and beyond question.

In relation to my valuing of staying in trouble, I also identify myself as being undisciplined. I like to experiment with what counts as “knowledge” and who counts as a “knower.” I frequently experiment with and attempt to transgress boundaries and unsettle “proper” ways of knowing and producing knowledge. I often like to put disciplinary forms of knowledge into conversation in unexpected ways and my work frequently resides at the limits of disciplines. I am also undisciplined in how I engage with and on social media. I frequently push at the limits of how blogs, for example, can (or maybe should) be used. Yet, even though I am undisciplined, my ability to do so comes from extensive disciplinary training and results in repeated, very purposeful practices.

One way of doing feminist interdisciplinary work:

I do not wish to present my work on trouble and digital media as the model for how to do interdisciplinary feminist work. Instead it is one vision that hopefully serves as an invitation to others to critically engage and to offer up their own understandings of how we might do feminist interdisciplinary work. My vision comes out of an understanding of feminism as a collection of movements and communities that exist in relation to and beside other social movements and that gains vitality from not reconciling the various ways in which it gets expressed/realized/enacted/practiced. It is interdisciplinary because I draw from a number of different disciplines, including: philosophy, education, religion, ethics, cultural studies, media studies and political science. I understand the work that I do to include: not only the finished products of my research, but the thinking/connecting/experimenting/processing work that I also do. I aim to make all aspects of that work visible and accessible to others.

on and through social media

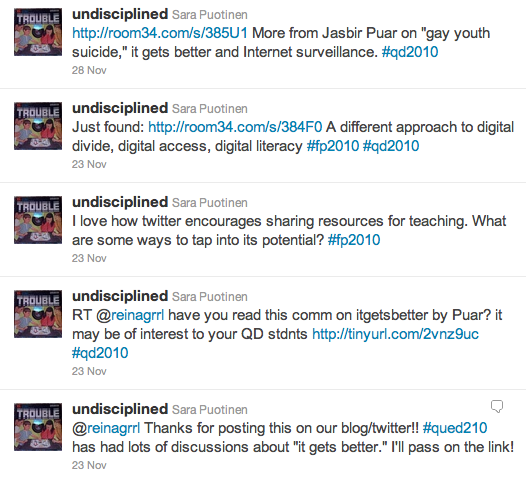

I engage in research that is on (about) digital media, particularly exploring the limits and possibilities of digital media for feminist pedagogical projects. I also use digital media to engage in and document that research and thinking. While I focus primarily on blogs and, more recently, some on twitter, I am also interested in critical explorations of facebook and youtube, digital storytelling, creating digital videos, video-logs, podcasts, and maptivism through google maps.

Why social media?

First, I believe that there is tremendous potential in digital/social media in shifting how we value and engage in learning and producing and sharing knowledge. I have already written extensively about blogs and how they can foster experimentation, enable us to get our work out to others immediately (more accessible to wider audience), allow others to engage with us, and encourage collaboration and sharing of resources.

Second, social media isn’t going anywhere. We need to develop strategies for critically engaging with it (not just rejecting it or uncritically embracing it). How do we respond to the ever-increasing presence of social media in our lives/classrooms/workplaces? How are social media shaping who we are, what we know and how we know it? In many ways, we are in a social media era where it is not so much a matter of being for or against social media; they affect us/shape how we are intelligible as consumer-citizen subjects and regulate what information/ideas/products that we have access to. So, the question is not: are we for or against social media, but how can we position ourselves in relation to social media in ways that are more resistant to its harmful effects while harnessing its potentially transformative possibilities? How do we use social media in resistant, transgressive and transformative ways? How do we develop strategies/ways-of-being that enable us to use/engage with social media for our feminist pedagogical-theoretical-activist practices and projects? What role can feminist scholar/educators/activists have in shaping how social media is practiced–in how people are trained to use them? What skills they develop as they post, tweet and update their statuses?

Third, in my own practices, I find digital media, especially blogs, to be very exciting and useful. Here’s what I recently wrote about why and how I use blogs:

Having used blogs in my courses since early 2007 and in my own research, writing and collaborative projects since 2009, I see them as potentially powerful spaces for radical transformation, critical and creative expression and community-building. They play a central role in all aspects of my life as a thinker, learner, writer, teacher and researcher. I write in three of my own blogs and I make blogs a central part of all my classes. I use my personal and course blogs to encourage myself and my students to archive our ideas, to document our research, to put seemingly disparate ideas or representations into conversation, to offer up various accounts of ourselves, to build relationships with visible and invisible/known and unknown readers, to experiment with pedagogical techniques, to cultivate effective writing and thinking habits, to disrupt the rigid rules and disciplinary borders that discourage new ideas and unexpected connections, to lay bare our own thinking and writing process, to practice what we teach (and preach), to develop connections between our different selves, and to remind ourselves that being thinkers/learners/teachers can be energizing and fun. In addition to all of these reasons, writing on my own blogs and using blogs in the classroom enables me to access my feminist troublemaking self. Through blogging, I reject rigid boundaries between disciplines, find creative ways to connect my research with my life, and infuse my ideas with a sense of humor. I play with what should count as rigorous scholarship or as proper objects of study. I cultivate a curiosity about the world that is motivated by a desire for engaging and experimenting with ideas as opposed to acquiring knowledge. And I invite my fellow bloggers (inside and outside of my classes) to join me at an experimental and unsettling space where we strive to remain open to new ideas and to critically exploring the limits of our own perspectives.

I didn’t start out a few years back, intending to think about/reflect on blogging and social media so much. Instead, I wanted a space to begin documenting and archiving my writing and ideas, ideas that had been brewing for years but that I never had time to formulate in concrete ways. I also wanted a space to experiment with new course assignments. However, once I began writing on this research/thinking blog, I knew that if I were to use blogs effectively, I needed to learn more about how they function, how others are using them, and what specific limits and possibilities they offer to an undisciplined and interdisciplinary feminist educator/activist/troublemaker. For the past year and a half, I have devoted a lot of time to researching, writing about and engaging in blogging practices. In the last six months, I have expanded my work to think more broadly about social media—twitter, in particular–and its limits and possibilities, particularly, but not exclusively, in relation to feminist (and queer) pedagogy.

Having explained my title as a way to introduce, in broad strokes, who I am as scholar and educator, I want to offer up several of my current research projects and the clusters of questions that these projects raise for me. As part of my own troublestaying and undisciplined approach to feminist work, I gravitate towards questions instead of answers. In the next entry, I will discuss my first research project.