I really like Cynthia Enloe’s notion of feminist curiosity. I teach it every year in my feminist debates class and I wrote about it on this blog a few years ago. In her discussion, Enloe describes how/why feminists need to be curious and to keep engaging in the difficult and exhausting labor of asking questions, challenging common-sense assumptions and taking the stories of a wide range of women seriously.

Here’s what I wrote about the essay and the need for curiosity in my post from a few years back: In her essay, Enloe is primarily concerned with exploring why so many of us have stopped being curious. As her title indicates, she is curious about our lack of feminist curiosity. Enloe attributes this lack to a variety of factors: laziness and an unwillingness to exert too much effort; the desire to conserve energy for more “important” activities; an over-reliance on what is “natural,” “traditional, “always” and “oldest”; a strong encouragement by those in power to not question or think about why things are they way they are and how they could or should be different; and a desire to remain comfortable (because thinking too hard and asking too many questions might be too disruptive or unsettling to ourselves and/or others).

Enloe reflects on this lack of curiosity by offering up an example of her own laziness. She writes:

for so long I was satisified to use (and think with) the phrase “cheap labor.” In fact, I even thought using the phrase made me sound (to myself and to others) as if I were a critically thinking person, someone equipped with intellectual energy. It is only when I begin, thanks to the nudging of feminist colleagues, to turn the phrase around, to say instead “labor made cheap” that I realized how lazy I had been. Now whenever I write “labor made cheap” on a blackboard, people in the room call out, “By whom?” “How?” They are expanding our investigatory agenda. They are calling on me, on all of us, to exert more intellectual energy (2).

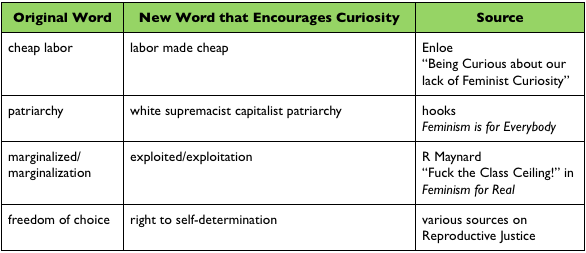

I really like this idea of creating phrases that encourage (and sometimes even demand) that we ask questions about our basic assumptions or the ideas that we become (almost) too comfortable with using. It is relatively easy to throw around the phrase “cheap labor” without really thinking about what that means and at whose expense. “Labor made cheap” invites us to take the topic seriously.

And here are a few shifts in language that encourage us to be more curious:

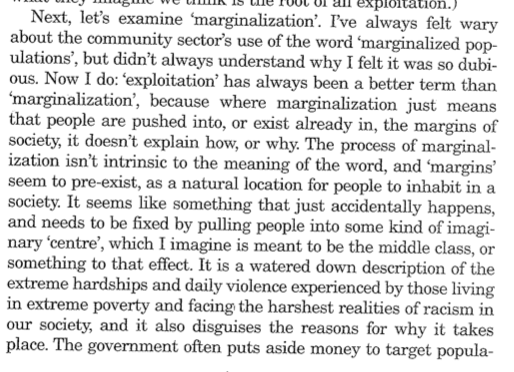

My inspiration for creating this blog post (and the above chart) was Robyn Maynard’s discussion of replacing “marginalization” with “exploitation” when thinking/writing/talking about “women, people of colour, Indigenous people and migrants” (118). In “Fuck the Glass Ceiling,” (Feminism for Real) she writes:

I think she makes a compelling argument for why using exploitation instead of marginalization encourages us to be more curious about how and why people suffer extreme poverty/face hardships.

Any other shifts in language that you think encourages us to be exercise some feminist curiosity?