For some reason, I am drawn to musical references. First, mash-ups and now remixes. Why? Not sure.

Last week I finally got my copy of Sara Ahmed’s latest book, The Promise of Happiness. I’m very excited to read it (and hopefully teach it) in the fall. You may recall that I have written about and taught parts of the book already. With all of my other writing to wrap up, I haven’t had a chance to do a close reading (or even much of a skim) yet. I anticipate that this book will be extremely helpful as I continue to think through troublemaking and its political and ethical value; I see lots of connections between Ahmed’s feminist killjoy and unhappy queer and my troublemaker.

Today I took a quick peek at the book. Since I am thinking a lot about virtue with my current mash-up, I decided to check her index for Aristotle. I found him. On pages 37-38, she discusses habit, happiness and Aristotle’s (mis) treatment of feelings. While Aristotle claims that being good and happy (and having a good life) are not the same as feeling good and feeling happy, Ahmed argues that he continues, through his emphasis on the regulation and balancing of feelings (between excess and deficiency), to link the two in ways that make one seem to naturally follow from the other: “we assume something feels good because it is good. We are good if it feels good” (Ahmed 37).

Check out what she has to say about feeling good and being good and their connection to the regulation of desire:

A happy life, a good life, hence involves the regulation of desire. It is not simply that we desire happiness but that happiness is imagined as what you get in return for desiring well. Good subjects will not experience pleasure from the wrong objects (they will be hurt by them or indifferent to them) and will only experience a certain amount of pleasure from the right object. We learn to experience some things as pleasure–as being good–where the experience itself becomes the truth of the object (“it is good”) as well as the subject (“we are good”). It is not only that the association between objects and affects is preserved through habit; we also acquire good tastes through habit. When history [of repeated habits?] becomes second nature, the affect seems obvious or even literal, as if it follows directly from what has already been given. We assume that we experience delight because “it” is delightful (Ahmed 37).

So, being good and feeling good are inextricably linked; when we feel good it is because we did something good and when we do something good our reward is that we feel good. One naturally follows from the other and we are able to neatly balance/regulate/guide our feelings in the “proper” direction. Ahmed sees this as a problem because the connection is not natural; it is produced through repeated habits that reinforce the connection between what feels good and what is good. Moreover, what is “proper” gets narrowly defined and is guided (almost exclusively) by a particular vision of the future–in other chapters (and previous excerpts that I have read), she discusses the heteronormative future, where the end goal/the happy ending is heterosexual marriage. Feelings get regulated through this narrow vision, making anything that doesn’t fall in line with it (say, anything that falls outside of Rubin’s charmed circle or that doesn’t reinforce heteronormative desires) as producing bad feelings or bad (as in unhappy, non-flourishing) lives.

Ahmed wants us to pay attention to feelings and how our responses to certain objects get regulated/shaped/determined in ways that dictate what sorts of actions and objects of our pleasure are deemed proper (and good) and which are not. And she wants us to challenge (make trouble for, perhaps?) the ways in which Happiness, as an end goal, so often only directs us towards certain paths (at the expense of others).

In what I have read so far by Ahmed on Aristotle (pages 36-37 and earlier versions of “The Unhappy Queer” and “Feminist Killjoys”), I don’t think that she wants to reconsider Aristotle. Aristotelean virtue ethics seems to be too mired in a limited and regulating view of happiness, one that overemphasizes naturalizing our habits and our emotions and directing them towards one universal vision of the Good. In thinking about these last two sentences some more, I happened across this passage by Ahmed which reinforces my own assessment. She writes:

I will not respond to the new science of happiness by simply appealing for a return to classical ideas of happiness as eudaimonia, as living a good, meaningful, or virtuous life….Critiques of the happiness industry that call for a return to classical concepts of virtue not only sustain the association between happiness and the good but also suggest that some forms of happiness are better than others (12).

So Ahmed is not interested in thinking (too much) about Aristotle in relation to her analysis of happiness and unhappiness (this is clearly evident in her index; out of 233 pages of text, Aristotle is only referenced briefly). But I am. How much attention do I want to give to Aristotle? At this point, I’m not sure. I do know that I want to take up Judith Butler’s challenge–the one that I mention here, here, and here–to rehabilitate Aristotle. While Butler suggests that we rehabilitate Aristotle through Foucault, I want to add a few more thinkers into the mix with him: Butler and Sara Ahmed. Hence, the title of this entry. My revisiting (remix) of Aristotle is one that involves an emphasis on and serious critical attention to feeling (both good and bad feelings) and how they circulate within our experiences of and discourses on goodness, flourishing and virtue ethics. I’m not sure if this makes sense yet….

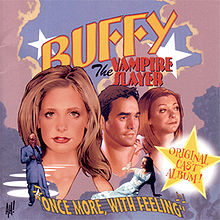

Because I was curious, I looked up the phrase, “once more with feeling.” I was pleasantly surprised to find that it is the title of the Buffy Musical Extravaganza from season 6. Cool.

Comments are closed.