Right now I am writing about Butler, being beside oneself with grief and being/coming undone. For some reason, this section is giving me a lot of trouble. I think it is partly because it can be easy to get lost in Butler’s theorizing about the subject–I find myself struggling to determine when something is really important and compelling and when it is merely an intellectual exercise.

Here is what I have so far (note: my notes about this section are included in italics):

In Undoing Gender, Butler describes feeling so overwhelmed and overtaken by losing a loved one that we are beside ourselves with grief. Our feelings of sadness and loss become too much to contain and we cannot hold them in. We lose our composure and we can no longer easily or successfully control ourselves. Try as we might to deny it or to be in control of how we experience it, grief undoes our efforts to handle ourselves properly. Butler writes:

I don’t think, for instance, you can invoke a Protestant ethic when it comes to loss. You can’t say, “Oh, I’ll go through loss this way, and that will be the result, and I’ll apply myself to the task, and I’ll endeavor to achieve the resolution of grief that is before me.” I think one is hit by waves, and that one starts out the day with an aim, a project, a plan, and one finds oneself foiled. One find oneself fallen. One is exhausted but does not know why (18).

My use of the word “properly” is deliberate here. In keeping in line with my larger project on troublemaking, I am interested in what it might (or is supposed to mean) to grieve properly. What happens when we fail to do it in the ways that we are supposed to? What is the “proper” way? I am struck by how I feel, even as I constantly hear/read from others that “there is no one way to grieve” or that “everyone grieves differently,” that there are specific expectations–coming from whom?–about what grief should look like. It is important for me to think about the value of grieving improperly–this can be taken up in a lot of different ways, from “proper” rules of grieving etiquette to “proper” modes of caring for and loving the one who is dying/died.

There are all sorts of ways to interpret what it means to be undone and beside ourselves with grief. For example, we can read it as a temporary state, as something that exists fully outside of, or in complete contrast to, our ordinary existence. Or we can read it as evidence of how debilitating and damaging grief is. Or we can even read it as a challenge that is thrown at us in order for us to prove our worth and our strength of character. With all of these interpretations, grief is understood as something to endure, but to be gotten over, preferably as quickly as possible.

Butler’s invoking of the Protestant ethic is great here–makes me think of the idea of getting over it or just dealing with it. I just read, “Good Grief, It’s Plato,” a chapter from Elizabeth Spelman’s excellent book,Fruits of Sorrow. Spelman discusses Plato and his vision of proper grief as moving on and learning from that grief (as opposed to engaging in any excessive displays of grief–like crying or wailing–which is considered to be too womanly/feminizing).

Butler reads coming undone differently. She envisions it as “one of the most important resources for which we much take our bearing and find our way” (Precarious Life, 30) and argues that it reveals an important aspect of what it means to be human. Being beside ourselves with grief, in which sadness and a sense of loss, undoes us, reminds us how we are always already, by virtue of being human, “in the thrall of our relations with others that we cannot always recount or explain,” or, I might add, control, shape, or determine (19). In other words, grief reminds us that we are more than autonomous willful individuals who have complete control over ourselves–how we act, what and when we feel, and how we represent ourselves to others. It also reminds us that we are never just a self; there is always something or someone beside and besides us.

In continuing her description of how grief works, Butler speculates on that something/someone else:

Something is larger than one’s own deliberate plan or project, larger than one’s own knowing. Something takes hold, but is this something coming from the self, from the outside, or from some region where the difference between the two is indeterminable? What is it that claims us at such moments, such that we are not the masters of ourselves? In what are we tied? And by what are we seized (18)?

Butler’s language is significant here. In using tied and seized, she is interested in getting beyond the idea that we merely exist in relation to others, that we are connected to others. Right after this passage, Butler moves into her brief description of being beside ourselves and ecstasy as a better way (than relationally) for understanding how we exist in relation to others. In the interest of staying focused, I am thinking that I shouldn’t include this discussion in this essay. Still not sure…

This something or someone to whom we are tied and to whom we are seized indicates that we are vulnerable beings, always in the midst of others and always potentially undone by those others. We could, and often do, respond to this recognition of our vulnerability with varying degrees of violence: we deny that vulnerability and attempt to shore up our own sense of the invulnerable self, we lash out at those who remind us of that vulnerability, or we attempt to prove, through forceful acts, that we are not really vulnerable, or won’t ever be again. These are not the only possible responses to grief and coming undone, however. Butler wonders,

Is there something to be gained from grieving, from tarrying with grief…and not endeavoring to seek a resolution for grief through violence?…If we stay with the sense of loss, are we left feeling only passive and powerless, as some fear? Of are we, rather, returned to a sense of human vulnerability, to our collective responsibility for the physical lives of one another” (23)?

Here Butler is thinking specifically about the United States government’s response to 9/11 and their violent retribution which she mentions in her chapter in Undoing Gender but really gets into in Precarious Life. Just consider this quotation that is featured on the back cover of that book: “If we are interested in arresting cycles of violence to produce less violent outcomes, it is no doubt important to ask what, politically, might be made of grief besides a cry for war”

For Butler, recognizing our vulnerability and refusing to conceal, contain or get rid of it, is an important task of the ethical (and political) subject-self. It is central to her vision of the human and to her political and ethical projects for social transformation. And is is “one of the most important resources form which we must take our bearings and find our way” (23).

So, that’s it for now. My next section will be about why Butler’s vision/version of grief doesn’t fit with my own experiences.

By the way, I am currently writing this at Overflow Espresso Cafe–a coffee place not to far from the U of Minnesota. It’s pretty cool and relaxing, especially when school is out for the month. Check out STA’s review of the place.

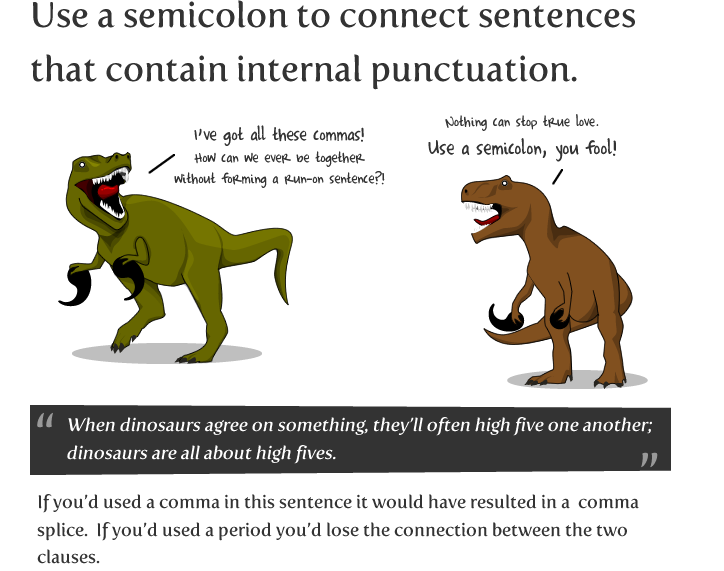

Here’s one more thing I meant to add into this entry earlier. As I was writing this entry, I found myself wondering about semicolons and when and why to use them. STA directed me to this great poster. I think I want it for my office. I love these queer dinosaurs!

Comments are closed.