I am continuing to document and archive the writing process for my manuscript on grief, loss, and my mother’s death from pancreatic cancer. This is entry four. So far I have written about the title and posted fragments of the essay and my thoughts about it. In this entry, I want to offer up a few more fragments and describe how I will organize the essay. Before moving onto that discussion, I want to document some other details about this process:

It is a beautiful day. Mid-70s, sunny, with a slight breeze. I am listening to Regina Spektor. I began this morning, with my daily latte, writing in the backyard. I used my iPad. Now I am inside the house, in my office. I tried writing this entry on my iPad, but I am having some issues with the WordPress app (by issues I mean that I clicked out of the app briefly to refer back to my manuscript, which was in Pages, and lost my entire entry). As I type these words, I am using my MacBook. Perhaps I just need to get used to the WordPress app, but I can’t be bothered with that at this moment.

Is this more detail than you would like? Or, maybe not the right kind of detail? I am experimenting with how to document my writing process–what to include, how to insert myself as a person-who-is-writing into this post. What do you think?

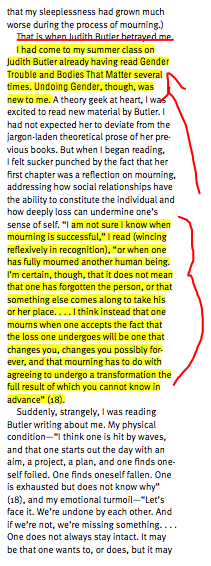

So, onto the manuscript. I plan to organize the heart of my essay around two different meanings for beside: a. to be beside oneself with emotion and b. to be beside someone else, keeping vigil and taking care. Right now I am working on (and struggling a little) with the section on being beside oneself. Central to this section is Judith Butler’s ideas about being beside oneself with grief and her valuing of grief/coming undone as “one of the most important resources from which we must take our bearing and find our way” (Precarious Life, 30). Butler argues that being in a state of grief (being overcome with grief, overwhelmed by sadness, losing control, being vulnerable, coming undone) reminds us how we are always already, by virtue of being human, “in the thrall of our relations with others that we cannot always recount or explain,” or, I might add, control/shape/determine (Undoing Gender, 19). For Butler, to be undone by others is a central part of the human experience and grief is one of the primary ways in which we are aware of/experience that undoneness. To fail or refuse to acknowledge that we are undone is to miss something really important (I mention this in entry two here).

While I agree with Butler’s assessment of grief, having experienced coming undone by grief too many times in the past four years, I find it to be lacking. Grief is not the only resource we have for making sense/being reminded of our vulnerability. It is not the only way in which we are beside ourselves. While Butler agrees, and briefly mentions rage and passion in her discussion, she focuses almost exclusively on grief (read as sadness and loss). Some attention needs to be given to these other emotions and how they are not merely additional resources (ones that exist besides grief), but they are resources that exist in the midst of (beside) grief. Here’s another emotion/feeling/affect that I want to add: joy/laughter. In my experiences of being beside the Judiths, my mom and even moreso my daughter have undone me with playfulness and laughter. They have caused me to beside myself with joy as I marvel at the beauty of life instead of the sadness of death. Now, my ideas here are not necessarily in opposition to Butler’s. She has a different project and is placing her ideas of grief and being undone in a different context. Instead, I see my inclusion of joy as another example of beside–I want to place my thinking about being undone in terms of joy/laughter next to Butler’s.

I am still working through how to articulate joy. Somehow I want to connect it to the idea that vulnerability can and should be understood in relation to death. However, it should also be understood in relation to life. Our experiences of grief and joy are not in opposition to each other and don’t occur at different times. They interrupt each other in unexpected ways. Grief/death may interrupt life (and our comfortable, in-control living of it), but life can also interrupt grief/death. Here are a few narrative fragments I want to weave into this section of my essay.

First, one about joy/life unexpectedly happening:

The social worker told us–me and my sisters–that we needed to let our mom know it was okay to let go. We needed to tell her that she had our permission to die, that we were okay with it. My sister planned a big dinner for mom and the three of us readied ourselves for the painful conversation. Just before dinner I turned on some music–The Sound of Music, one of my mom’s (and my) favorite musicals. Spontaneously I, sometimes with my sisters joining in, performed the entire musical. At one point, maybe when I was singing “The Lonely Goatherd” I realized that this was one of those big moments in my life. My mom may have been dying, but she was laughing too. Well, at least her eyes were laughing. And we were all having a lot of fun. At the end of the album, when Mother Superior sings “Climb Every Mountain,” I hit the high note! I mean, I really hit the high note–vibrato and all. We laughed and laughed and then brought my mom her dinner, forgetting all about “that conversation.” Sometimes life interrupts grief, not the other way around. Our best intentions of properly grieving are undone. Our attempts at making sense of how grief is supposed to be are troubled by life’s persistent refusal to stop happening.

Second, one illustrating how life continues, and is not thwarted by, death:

My mom was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer in mid-October 2005. I was around 18 weeks pregnant with Rosie. A few days before I drove to Chicago to see her, maybe for the last time, I had an ultrasound. I found out that my baby was a girl. When I arrived at my parent’s house, I told my mom that she was going to have another granddaughter named after and in honor of her: Rosemary Judith. I was fairly certain that my mom would never meet her; the doctor had indicated that she might only have six weeks left. Six months later, my mom took a break from chemotherapy to visit us and meet her new granddaughter.

As I mentioned above, I’m still not sure what to do with these fragments. In particular, I think there’s more going on in the second one that I readily convey–something more than just the juxtaposition of life with death.

Oh, in case you can’t remember the high note at the end of “Climb Every Mountain,” here it is. And yes, I really did hit it: