Quite frequently I require my students to “engage” with readings, authors, and concepts from class. I prefer this term over other options, like critically assess, analyze, critique, or even describe. But, what does it mean to engage? Last semester in my big class, one of the TAs had to devote about 30 minutes of her 50 minute discussion section to explaining the term “engage.” At first, when she told me that the students had required that she spend so much time discussing how to engage I was incredulous. Really? I wondered. How can students come to college and not know what engage means? However now, as I think through some of the readings that I’m using for my feminist pedagogy article, I’m reassessing my reaction. Maybe understanding what it means to engage is not as easy (or obvious) as I thought. Maybe I need to spend some time unpacking the term (ugh….I don’t really like using the term “unpack,” but it seems to fit here)? Maybe I also need to think through why students wouldn’t necessarily understand what it means to engage. Or what resistances they might have to engaging in the first place. In (hopefully) a series of posts, “What does it mean to engage?”, I want to spend some time and space engaging with the term “engage.”

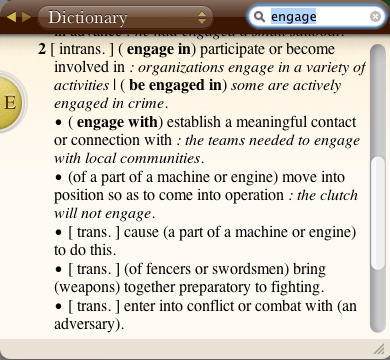

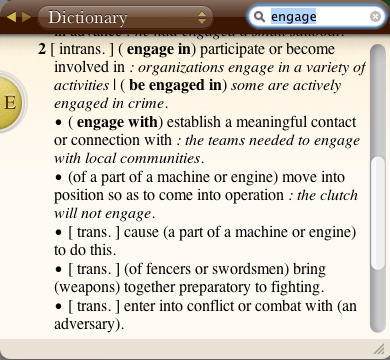

So, again, what does it mean to engage? Maybe a good place to start is the dictionary; I’ll use the one on my computer dashboard. While not all of these fit, I do find that several of the definitions can help to clarify what I mean when I ask students to engage. To engage with an author or an idea or a conversation or a reading is to do more than just read or attempt to comprehend what someone believes or what they assert in an essay. To engage is to participate/become involved (def. 2.1) with those ideas, to establish meaningful connections with them (def 2.2) in ways that require thinking about not only what they mean but what they do and what they do to us. In other words, when I ask students to “engage with an essay,” I want them to do more than read the essay, I want them to really try to understand what the author is claiming and then think about how that claim affects how they see/experience/feel the world. To engage is also to critique a reading/idea/author, not by dismissing it immediately as wrong, but by working through it, exploring its limits and possibilities and by debating it (def 2.6). Perhaps the biggest key to engaging is to be an active, involved, serious participant in the process of learning/thinking/feeling about an idea/author/reading.

So, again, what does it mean to engage? Maybe a good place to start is the dictionary; I’ll use the one on my computer dashboard. While not all of these fit, I do find that several of the definitions can help to clarify what I mean when I ask students to engage. To engage with an author or an idea or a conversation or a reading is to do more than just read or attempt to comprehend what someone believes or what they assert in an essay. To engage is to participate/become involved (def. 2.1) with those ideas, to establish meaningful connections with them (def 2.2) in ways that require thinking about not only what they mean but what they do and what they do to us. In other words, when I ask students to “engage with an essay,” I want them to do more than read the essay, I want them to really try to understand what the author is claiming and then think about how that claim affects how they see/experience/feel the world. To engage is also to critique a reading/idea/author, not by dismissing it immediately as wrong, but by working through it, exploring its limits and possibilities and by debating it (def 2.6). Perhaps the biggest key to engaging is to be an active, involved, serious participant in the process of learning/thinking/feeling about an idea/author/reading.

When I was in grad school, one of my professors provided me with a helpful framework for engaging with an author/text. I use this framework to think through my own writing and as I develop assignments for my classes. Here’s an example of how I used it in a class last fall. It involves three key elements: appreciation, critique and construction:

APPRECIATION involves figuring out what the author is saying and demonstrating a clear understanding of their argument and how they develop and defend it. Appreciation does not require that you agree with the reading. Instead, it requires that you clearly state the author’s argument. What is their main argument? What is the purpose of that argument? How do they defend it? This element of engagement is crucial; you can’t have a critical conversation about (or with) an author until you spend some time really thinking about what they are claiming.

CRITIQUE involves assessing what the author is saying. Critique should not involve a total rejection of dismissal of the reading. Instead, it could involve raising some critical or questions and/or exploring the benefits or limitations of the argument. An important thing to note here: critique does not mean trash (or reject or dismiss). Critique involves entering into a critical conversation or debate with the argument; it’s hard, if not impossible, to do that if you enter the conversation with the intractable position, “this author is absolutely wrong!”

CONSTRUCTION involves applying the concepts from the reading to your own thoughts, areas of interest and research or experiences. It could also involve applying the reading to the topics/discussions of our class. This element is especially important for engaging. Construction is about doing something with the author’s argument: applying it, translating it, re-working it to function in unexpected ways, taking it in new directions.

But, this isn’t all that engagement is, especially engagement from a queering feminist perspective. To engage with ideas is to resist them: to refuse to merely accept them as the truth, to push back and talk back at them, to trouble and disrupt them. It is also to be generous with them: to be open to taking them seriously and to allowing them to disrupt your worldview. I have a lot more to write on engagement, especially in relation to both my own troublemaking pedagogy and bell hooks’ notion of engaged pedagogy. But that will have to wait for part two of this series.