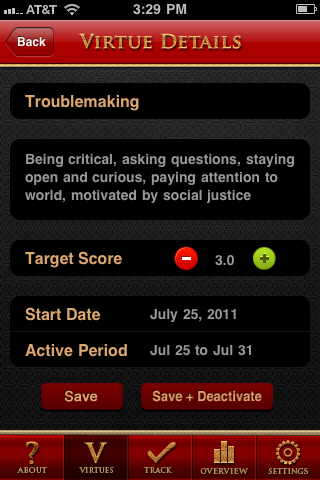

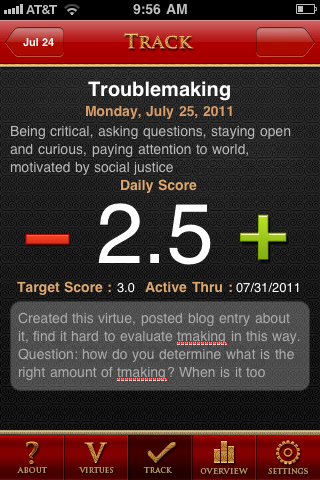

It’s day two of tracking my troublemaking practices on the Virtues app. Not convinced that this is the right approach for my reflecting on/assessing/building up my virtuous troublemaking. I must spend some time researching and thinking about other approaches. Anyway, I ranked myself at 3 out of a target goal of 3. Yay me! (Yes, this is a reference to London Tipton from Suite Life…RJP loves her and the show and it’s on instant netflix so I see it all of the time.) Like I did on my first day, I used the “reflection box” to pose questions about the app. I like creating space for these questions–but is it preventing me from taking the app seriously? How do I assess my troublemaking from yesterday? I still can’t imagine how you evaluate something like making/being in/staying in trouble (especially my version of staying in trouble, based on critical thinking, curiosity, pushing at my limits of knowing, being open to other ways of thinking).

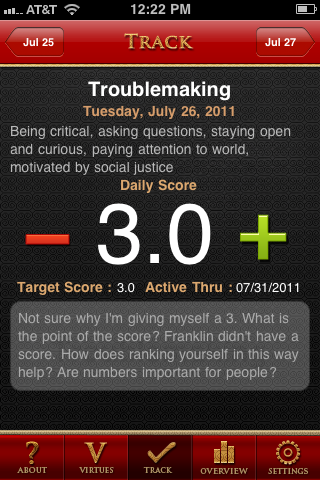

Here are my comments from the reflection box:

Not sure why I’m giving myself a 3. What is the point of the score? Franklin didn’t have a score. How does ranking yourself in this way help? Are numbers important for people? What if you encouraged people to reflect without number rankings? Where do we learn what a virtuous action is? Doe we just know? Do we get it from our parents? What does Aristotle say? What does Ben Franklin say? Just downloaded free BF autobiography on iBooks.

All of these questions, make me even more skeptical of the ranking approach. They also make me think that I might need to narrow down the specific set of practices that I imagine to exemplify effective troublemaking for me. One goal of this evaluation process seems to be checking to make sure that your intentions and values are matching up with your actual practices. This goal reminds me of bell hooks’ discussion of habit, virtues and values in a “Revolution of Values” which I must reread) in Teaching to Transgress. I started writing about this section of hooks’ book way back on October 14, 2009 (just 2 weeks after my mom died). I never published it, but kept it as a draft on my wordpress dashboard. Here’s what I wrote in that draft:

This past week [for October 7th, 2009] my Feminist Pedagogies class read bell hooks’ Teaching To Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. I am struck by her discussion of values in Chapter 2 (entitled “A Revolution of Values”). Her emphasis on transforming oppressive values that guide our lives and the habits and daily practices that (sometimes unwittingly) reinforce those values is helpful in my thinking about why we need to engage in more talking and theorizing about virtues. I want to add hooks’ Chapter 2 to my list of theories/ideas/writings that inspire my own promotion of virtue (which I discuss at the end of this entry).

This past week [for October 7th, 2009] my Feminist Pedagogies class read bell hooks’ Teaching To Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. I am struck by her discussion of values in Chapter 2 (entitled “A Revolution of Values”). Her emphasis on transforming oppressive values that guide our lives and the habits and daily practices that (sometimes unwittingly) reinforce those values is helpful in my thinking about why we need to engage in more talking and theorizing about virtues. I want to add hooks’ Chapter 2 to my list of theories/ideas/writings that inspire my own promotion of virtue (which I discuss at the end of this entry).

Connection to virtue: In this chapter, hooks asks: “What values and habits of being reflect my/our commitment to freedom” (27)? She wants to shift away from reliance on “fancy” and “elaborate” theories that describe why we want freedom and focus instead on the values and habits that we actually practice on a routine basis (on the street, in the classroom). Her point, I think, is to suggest that theorizing by itself is not enough; we need Freieran praxis (theory, practice, reflection).

As I reflect back on these words [now on july 27, 2011], I am struck by how important reflection (and praxis as connecting theory and practice with reflection) are for assessing our own behaviors. For the Virtues app to be effective, a lot more attention needs to be given to learning how to be “honest with yourself”–which is the main advice that the app authors give for figuring out how to evaluate yourself (see yesterday’s post for more on this discussion). Being honest with yourself is not as easy as just committing to being honest. Instead it requires the tremendously difficult labor of developing both an awareness of your false consciousness/internalized sexism and racism and a critical consciousness of oppression and the need for social justice (this is a big goal for both bell hooks and Paulo Friere–with his idea of conscientization, or conscientização). In emphasizing a numerical ranking as the central part of the virtue evaluation process, the Virtues app encourages us to bypass reflection (and opt out of the difficult labor of thinking through how/why we fail to be honest with ourselves*) for an easy evaluation. I don’t care if my troublemaking is at a 2 or 3; I care about how/why I practice (or fail to practice) troublemaking in the ways that I do. And I care about finding ways to encourage myself to do the hard work it takes to make and stay in trouble in virtuous ways.

*I should say more about the various ways we are encouraged/trained/educated to be dishonest. Must leave that for another entry.

Note: my questions in the reflection box also made me what to think more about moral exemplars, education and our role models for developing virtuous practices. Could such reflection be incorporated into an app (maybe too much…need to think about this more).