Right now I’m in the midst of skimming through the article, Graduate School in the Humanities: Just Don’t Go (2009), and I’m wondering, Why did I go to graduate school? In the article the author, Thomas Benton (aka William Pannapacker), describes how and why he advises his students not to go to graduate school in the humanities. He writes:

What almost no prospective graduate students can understand is the extent to which doctoral education in the humanities socializes idealistic, naïve, and psychologically vulnerable people into a profession with a very clear set of values. It teaches them that life outside of academe means failure, which explains the large numbers of graduates who labor for decades as adjuncts, just so they can stay on the periphery of academe.

In an article published a year later (2010), Benton/Pannapacker intensifies his critique, writing:

Graduate school in the humanities is a trap. It is designed that way. It is structurally based on limiting the options of students and socializing them into believing that it is shameful to abandon “the life of the mind.” That’s why most graduate programs resist reducing the numbers of admitted students or providing them with skills and networks that could enable them to do anything but join the ever-growing ranks of impoverished, demoralized, and damaged graduate students and adjuncts for whom most of academe denies any responsibility.

Harsh. And (mostly) true to my experiences on the job market post-degree. Getting a Ph.D in the interdisciplinary field of women’s studies, I was shielded from some of this structural damage (or I managed to ignore it?). Maybe it was because I was being trained to identify and resist larger structures of oppression, privilege and unequal power distribution. Maybe it was because my committee members were supportive of my work and encouraged me, for the most part, to do the types of projects that I wanted to do. Maybe it was because I was one of “those privileged few” to which Benton/Pannapacker refers, that are fully funded and have a partner with a full-time job.

I did feel the pressure to professionalize—network! network! network! and publish! publish! publish!—and to pick projects that were cutting edge and grant-worthy. And I did feel that when I graduated in 2006, I wasn’t qualified for anything else. I was 31 years old and had been, almost exclusively, a student since I was 5. While some other students in my department had acquired valuable administrative skills, I had focused almost all of my attention on researching, writing and teaching (oh and having two kids). As the post-Ph.D years went by, and my job search for a tenure-track position continued to be unsuccessful and extremely demoralizing, I kept wondering, If I can’t teach at the college level, what can I do?

Like a good little student, I kept preparing and sending out ridiculously labor intensive application packets that continued to be rejected (sometimes without acknowledgment, sometimes after grueling campus visits). It felt hopeless. I felt hopeless. But I also felt like I couldn’t stop trying. I had been told too many times, once you stop applying and working for a job, you can’t try again. Your degree has a limited shelf life and nobody will want you if you’re not active in your field as a researcher or teacher.

It has been a year since I stopped teaching. A year since I sent in an application for an academic job. And, I’m relieved. For the past year, I’ve been working on a lot of different critical and creative projects that allow me to use the tools/theories that I learned in graduate school in ways that I never had time to do when I was teaching and that wouldn’t be valued within academic spaces. I’ve also experimented a bit with how to translate my skills into work outside of the academy.

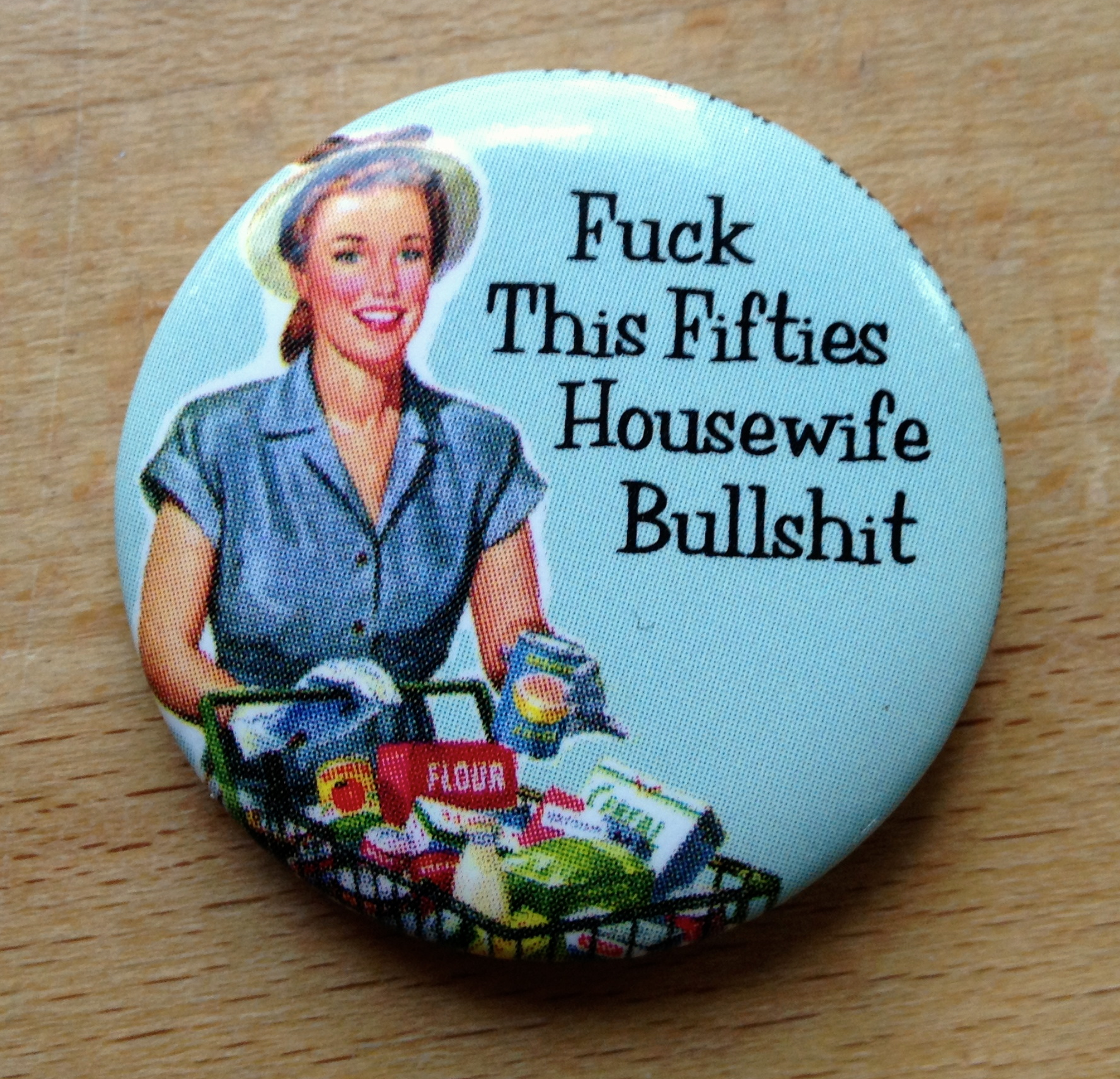

Perhaps most importantly, I’ve devoted tons of time to the difficult labor of unlearning some of the most toxic (at least for me) values of the academic industrial complex: that you’re a failure and less-worthy without a tenure-track job; that academic work is better (and loftier) than other professions; that the only thing you can do with a Ph.D is teach at the college/university level; and that even though the academic life is demanding and difficult, it’s worth it…for the difference you make in student’s lives, for the benefits you receive, for the flexible hours you can have.

So, as I posed at the beginning of this post, why did I go to graduate school? In one of his articles, Benton/Pannapacker speculates that many students go to graduate school because: 1. School is what they know; 2. School is where they are praised and validated; 3. It’s better than trying to find a job; and 4. They “think” they have a passion for a subject. In my case, I’m sure #1 applies to me. Not only had I been attending school since I was 5, but I, and my mom and 2 sisters, had been following my dad around the country my whole life as he worked in higher ed administration. School was all that I knew.

But, when I applied for graduate schools, first for a masters in 1996 and then for a Ph.D in 1999, I wanted to go because I believed (maybe a little naïvely) that the deep immersion in ideas and theories that grad school encourages, would provide me with the tools to make sense of my world/s and experiences and to have deeper, more meaningful conversations with a wide range of people. What I didn’t realize when I was applying is that I also wanted to go to graduate school to develop the skills that I needed in order to challenge those systems and structures that invalidated my curiosity, my penchant for posing questions and my refusal to ever accept that “that’s just the way things are.” My graduate training (and my later on-the-job training as an educator) in women’s studies and feminist/queer theory, gave me those skills. This training also forced compelled to recognize the limits and problems with the academy and to search for (and hopefully find) ways to resist and refuse it. At this point, I can’t say that it gave me the skills for reworking it. I’m not sure that it’s possible to rework a system so seemingly broken.